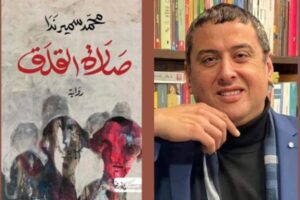

With 2025 IPAF Winner Mohamed Samir Nada

Watch the 2025 IPAF Ceremony here.

ArabLit & ArabLit Quarterly

May 7, 2025

In conversation with Elena Pare

Egyptian author Mohamed Samir Nada’s dystopian novel Prayer of Anxiety won the 2025 International Prize for Arabic Fiction. It is his third novel, although — in this conversation — he reveals an unpublished prolificity, alongside his job as a financial director in the tourism industry. Comparing writing to the sculptor’s craft, or to that of a tightrope walker, he reflects on censorship, irony, liberation, and anxiety.

This interview was conducted before Mohamed’s IPAF win was announced.

Elena Pare: Congratulations on Salāt al-Qalaq (Prayer of Anxiety) making it to the IPAF shortlist! How do you feel after this achievement and towards the prize more generally?

Mohamed Samir Nada: I feel charged with purpose, with the sense that the act of writing is not futile after all, as long as it can reside in the readers’ hearts. The prize has granted me a ‘diplomatic’ passport that will expedite my movements from place to place without needing a visa or standing in long airport lines. Writing is essentially a journey to potential worlds where language is the body and the imagination its spirit, but it extends an invitation for others to participate in the journey. This is what the Arabic Booker has granted me: it has widened my readers’ circle and thus the text’s ability to travel to more than one land and fancy. I quote the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish momentarily feeling writing’s futility and questioning his friend, the poet Samih al-Qasim, ‘Do you still believe that poems are more powerful than planes?’ I myself got close to believing that orphanhood was writing’s limit and fate, were it not for this prize which has given me a family of readers in every country. This exceptionally intense experience has made me believe that words are indeed more powerful than planes, both in transit speed and in their durability in readers’ lives. My writing no longer surrenders to the bitter feeling of isolation but rather has come to be in continuous flux towards the self, the other, and towards the wider world. ‘When did the flow of natural longing ever come to an end?’ Is this not what our forefather Abu Hayyan cried out in a text that still travels from his time to ours?

How do you imagine or hope it will influence your work and life?

MSN: This experience has given me a sense of meaning, in the presence of which darkness vanishes and all obstacles collapse. I now have readers who, awaiting my writing, look up what I’ve published previously. I must write for them as well as for myself, so that together we can open up the circle of beauty in a world enclosed by wars and pandemics, where ugliness tries to strip us from what is most sublime: the human being.

How did your literary journey start? What/who were your first experiences with books and reading?

MSN: Like all the children of my generation, I started reading Dr. Nabil Farouq. But being the son of a proficient litterateur, his huge library was the focus of my curiosity, and I chased after him, hungering to read his books. In middle school, having exhausted him with my persistence, the first book I remember being allowed to read from his library was Naguib Mahfouz’s collection The Pub of the Black Cat. I continued my journey from there and accumulated a long list of favourite writers in the subsequent thirty years.

As Egyptians go, my father comes first, then Mohamed Mansi Qandil, Abdel Hakim Qasem, Naguib Mahfouz, Adel Esmat, Sabry Musa, Khairy Shalaby, Ibrahim Abdel Meguid, Ibrahim Aslan, Badr Dib, Ala Dib and many others. As for Arab authors there is Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, Hanna Mina, Tayeb Salih, Fawwaz Haddad, Inaam Kachachi, Ibrahim Nasrallah, Amir Taj al-Sir, Saad Mohammed Raheem, Rashid Al-Daif, Jabbour Douaihy, Rabee Jaber, Muhsin al-Ramli and Hassan Mutlak. In the generation closer to mine, I really like the writings of Ahmed El-Fakharany, Tarek Emam, Mohamed El-Fakharany, Miral Al-Tahawy, Nora Naji, Azher Jirgees, Jan Dost, Abdel Wahab Al-Hamadi, Mohammad Tarazi, Maha Hassan, Walid Shurafa, Ala Hlehel, Samar Yazbek, Said Khatibi, Amira Ghenim, Hedi Timoumi, Saud Alsanousi as well as tens of other novelists. No short story writer is closer to my heart than Ziad Khaddash, while I love the poetry of al-Sayyab, Nazik Al-Malaika, Darwish and the Tuqan brothers. As for global literature, the Portuguese intellectual Pessoa comes first, then Kundera, Schmidt, Saramago and many Latin American novelists.

How did your literary taste and writing talent develop?

MSN: Writing is the child of reading. A talent in storytelling may be fundamental – our village grandparents’ tales are unmatched – however, this talent can only be polished by reading. If my writing skills have developed at all it has been the result of reading an endless variety. Literary taste depends on individual preferences, and I personally am not constant in my mood. I sometimes tend towards reading about what is preoccupying me and what perhaps resembles me, while other times I prefer reading what I do not know. I cannot say with certainty that my literary taste has evolved, such an evolution being a linear concept, but I can say that it has expanded and become more varied, richer, and more conscious. In the end, all writing is a piece of a unique incandescent lived human experience, and the multitude and diversity of written works are journeys to different human worlds that humble and enrich us. To me, writing is the product of each of these experiences and readings, so if a reader likes my writing, they must be aware that it is the heir to everything I have read to this day.

Prayer of Anxiety is your third published book, but it wasn’t easy finding it a publisher and a few years passed before Dar Masciliana in Tunis published it. Can you tell us more about this process, and about the works that remain, in your own words, in your drawer?

MSN: A painful and bitter experience has turned into a memory that leaves me beaming! Some might consider me foolish, but I do not waste my time chasing after publishers. As soon as I felt that Prayer of Anxiety was finished, after years of writing and erasing, I sent it to four or five publishers. I then received rejection after rejection, and some publishing houses did not even care to respond. So I put it away, in my drawer as I say, and started writing the next novel. Though I feel sad when I fail to publish my works, I don’t stop writing, as I’ve always thought their publication simply postponed to another day. But when, and with which publisher? I didn’t know it then, but I sustained this dreamer’s confidence in order to make space for writing. Then Masciliana unexpectedly contacted me. In fact, a happy coincidence led to my acquaintance with Shawqi al-Anizi, so I sent them the manuscript after all doors had shut in my face. Fate led me to a serious publisher who, from the very beginning, believed in my text and took good care of it, trusting it enough to nominate it for the prize. Publishing with Masciliana energized me, as it affirmed that there is still hope as long as I fuel my faith in my writing. As for my unpublished texts, I have a novel titled “A Tale of Freedom” that I tried to publish but it bumped against the publisher’s censorship guidelines; I refused the suggested edits and returned it to the drawer. I have eight other short novels of this kind that I’ve tried publishing in a collected volume, unsuccessfully to this day. I also have a chest in which I keep the ideas that I intend to write – if only life were long enough!

You once explained that when you started writing this novel in 2017, you wanted to challenge accepted realities with lightness and play, parody and fantasy being preferable to head-on confrontation. The imaginary dystopian village of Nag’ al-Manassi is a microcosm of apocalypse-threatening crises and disasters: from censorship and war to meteor showers and epidemics, and even Judgement Day. These are all dystopian tools to rethink the 1967 Naksa and criticize the dark state of the world. Why did you choose to set your novel in Upper Egypt in the decade following the Naksa? What inspired this setting and its characters?

MSN: The specificity of the place was not fundamental because the novel’s main concern is essentially Arab. From this perspective, the reader can picture the existence of Nag’ al-Manassi in any Arab or other state, despite its connection to Upper Egypt in the text. The Naksa was a turning point in Arab history, and it is in my opinion the continuation of the 1948 Nakba. By connecting the time to a period of rupture, I created a world of the defeated and broken, essentially trapped in their own thoughts. The meteorite was merely a slap in the villagers’ face, as was the epidemic – I came up with these events and phenomena to provoke my characters to react. The irony here is analogous to a lament of the situation, in a text that combines seriousness and wit. And perhaps the peak of this irony is to conceive and perceive people living in a prison of their pre-programmed minds. I wanted to assert that the liberation of land depends on the liberation of the mind. So even if a society successfully recovers their land and resources, it will not develop or progress as long as their minds remain victims of hijacking and corrupting the collective consciousness. These ideas, perhaps I should say obsessions, inspired the characters and built this strange world.

What can we learn about our current era from dystopias set in the past, in your opinion?

MSN: In my opinion the starting point of any learning process is awareness. Before we talk about any act of liberation or raise grand slogans that do not advance us one bit, we must be aware that we are manufactured things just like any packaged commercial good. Once we understand this, we can start removing our shackles, and know that we are diverse, unique human selves and not one and the same. And so, we start to accept the other, and if they were to be different, we do not act like Aunt Widad in the novel. We must be anxious because anxiety is fuel for questioning, and questions are fuel for the mind. And the mind does not welcome the same answers to the same questions across centuries. Including the past to our present moment reveals that we are creatures of repetition, repeating mistakes, frustrations and setbacks and repeating failures. This brings us to the Greek poet Yiannis Ritsos’s dangerous saying, ‘memory of the future’. This expression is elucidated more thoughtfully in the Moroccan intellectual Abdallah Laroui’s book Contemporary Arab Ideology in which he proposes the concept of ‘past future’ to explain our current intellectual condition.

Why are you interested in ‘anxiety’ and what does it mean?

MSN: ‘Anxiety’ is rooted in Arab heritage. It is a present-continuous-tense verb in Arabic, equivalent to the general state of amorphous fear that none of us is able to free themselves from. We’re anxious because we’re kept in the dark! Anxious because we are not and cannot be active, anxious because we are not happy, and know not where to find happiness outside of sensual pleasure. Anxious because we see but do not speak, because we speak but are not heard, and we hear but do not listen to the speaker! It is an endless circle in which activism is absent and fear spreads, spiraling outwards as the apparent agent shrinks into a concealed pronoun, and like the Arabic hamza, is seen but too weak to speak.

You’ve previously described your writing as being on the edge of an abyss, or like a snake slipping through your hands. What do you mean by these two images?

MSN: I associate these two images with the concept of play. Writing is essentially a kind of game because it follows procedures specific to its central element, like a child who builds a sandcastle on the beach only to see it destroyed by the wind. But this game is not fun and free as it is for the child, rather it is a tragic game that plays with passions, destinies, and potential realities. So I also compare it to an acrobat balancing on a tightrope over the precipice, or to a snake slithering through your fingers. Play is writing’s motor because it provides pleasure, which is subjective, locking the process into the self. To include the other in our pleasure, a message must be sent, even if it is hurtful or shocking. Do we not play with our suffering to forget the pain, like the charmer tames the snake so that it forgets to bite?

Tell us about the process of writing a novel, and specifically Prayer of Anxiety. How did you start? What challenges did you face? When did you know you had finished?

MSN: I knew I’d finished writing when I stopped erasing and deleting, like a sculpture finally completed after the sculptor went over it with his chisel and eye to carve out the deposits of the creation process. I perhaps envy this sculptor for his ability to destroy his sculpture after exhibiting if he were to find some crookedness – I cannot delete my novel upon publication if in its pages I come across a mistake that passed me by. My writing rituals are primarily about finding peace and quiet. In Prayer of Anxiety, I shifted between literary styles until the story settled into what it has now become. I did not face any challenges while writing other than taking the necessary time from my noisy and tiring life. After this came the challenges of publishing, but this is now a thing of the past.

You recently mentioned that you are writing a book set between Turkey, Iraq, Palestine, and Egypt between 1914 and 2013, as well as another dystopia set in 2152. Can you tell us more about your upcoming projects?

MSN: I cannot promise a historical novel because an understanding of the past is fundamental to any discussion of the present. So the novel starts in contemporary times then returns to the beginning of last century to contextualise its world clearly. It can then posit its principal issue about the sanctity of blood between squandering and forbiddance. This is an issue that I imagine most publishers will not welcome openly, however I trust that some like Masciliana will have the necessary courage to publish such a text. The other novel is dystopian with a comic edge, and imagines a dark fate for Arabs in light and foresight of what we’re living through now. This novel makes me laugh as I write it, though its core meaning is not funny.

Elena Pare is a French-Swiss-British graduate of the University of Cambridge in Arabic and Persian and an emerging translator of fiction from French, German and Arabic into English and French.

Also watch: A short film interview with Mohamed Samir Nada