Who do stories belong to?

Samah Selim re-maps the journey of the early Arab novel

Friday, March 6, 2015

By Laura Gribbon, Jadaliyya

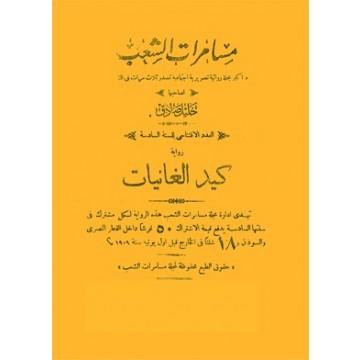

Do stories need authors? Are texts fixed? Is adaptation a form of translation? These are some of the questions Professor Samah Selim has been considering in her study of Egyptian periodical Musamarat al-Shaab (The People’s Entertainment), and she raised them during a talk at the American University in Cairo last week.

Although it has a long and varied history, adaptation is a contentious issue today amid copyright and publishing norms. Selim suggests that the Arabic novel has lost an organic fluidity with the development of a literary canon and intellectual ownership.

Many have accused Ahmad Mourad of reproducing characters from Naguib Mahfouz in his novel 1919 (2014), and borrowing from Peter Burger’s New Zealand film The Tattoist (2007) — which, Selim notes, mimicked a number of other films before it — in writing Al-Fil al-Azraq (The Blue Elephant, 2012). There has also been much discussion about the influence of Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club (1996) on Ahmed Alaidy’s An takun Abbas al-Abd (Being Abbas al-Abd, 2003).

Going back in time, during the late 19th and early 20th century Nahda (Arab renaissance), critics questioned whether the Arabic novel itself was merely a mimicking of a European genre.

But the novel’s journey into Arabic was actually “clandestine, meandering and mischievous,” Selim argued in her fascinating lecture for the AUC’s Center for Translation Studies, “The People’s Entertainment: Translation, Adaptation and the Novel in Egypt.”

Established by Khalil Sadiq in 1904 and published until 1911, The People’s Entertainment included at least 80 novels and short stories. Selim says around 12 were originals, 13 were close translations of foreign-language novels, 27 were adaptations citing an original author, and the remainder are not attributed, but loosely based on French or English fiction.

Certain adaption processes make the novel an “adaptable, anarchic and popular genre,” Selim said.

She cited Arsène Lupin, French writer Maurice Leblanc’s fictional character, whose adaptation in Arabic hasn’t been merely a “copying by the subaltern,” but a way of drawing on older forms of local popular knowledge. Similarly, the first Arabic version of Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) was published in 1838 anonymously and followed by a host of other adaptations.

Imitation and adaptation were the norm everywhere before 18th-century Romanticism emerged, Selim points out, along with the parallel emergence of nationalism in Europe.

The People’s Entertainment had a large readership and was written by journalists, lawyers and men of letters. Its advertisements indicate an audience of largely middle-class professionals.

Fiction was hugely popular. Between 1858 and 1873, 30 new journals dedicated to publishing fiction in Egypt and Syria were established, along with numerous newspapers. The state-owned Al-Ahram newspaper, which started publishing in 1875, also regularly published translated or adapted fiction in its pages.

Discussion around Arabization, Egyptianization, and creative adaptation were prevalent during this period, with texts commonly presented as “authored by,” “rendered by” or “from the pen of” in pieces seen more as a “textual voyage” than a fixed moment of ownership, according to Selim.

She explains that some 20th-century Arab authors even published their own original stories as translations, as the genre was so popular.

Selim challenges the notion this was pure obsession with the “foreign.”

Firstly, the foreign novels selected for adaptation often contained an implicit critique of global modernity and predatory capitalism, which coincided with the catastrophic 1907 stock-market crash in Egypt. In this way, European and American cities, particularly Paris, were stripped of their specificity and came to symbolize the global system and a cultural voyage beyond merely the self and the other.

Secondly, Lebanese author Jurji Zaydan drew parallels between the European novels of the nineteenth century and oral Arab storytelling traditions, such as The Thousand and One Nights.

This form of domestic critique and self-reflection was not as concerned with the colonial discourse of power as the state project was. The fascination with adapted novels confused some critics and scholars, for example when state-supported novels such as Mohamed Hussein Haykal’s Zaynab: Manazir waaakhlaq rifiyyah (Zaynab: Country Scenes and Morals, 1913), were not as widely read as such “authentic,” national novels were expected to be.

Adaptation has always been part of the development of new genres, Selim claims. And although the power relations in the colonial and post-colonial context problematize translations and adaptations like those in The People’s Entertainment, and might prejudice people against them, they can also be used to subvert these power relations by destabilizing the original.

In a theory of mistranslation developed in The Translators of the 1001 Nights(1936), Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges emphasizes the “importance of the displacements that occur when one goes from original to translation, and how these displacements create the potential for new and unexpected meanings.”

What some have labeled textual disruption and mimicry, referring to authors like Ahmed Alaidy, has been compared by Tarek al-Ariss, associate professor of Arabic literature at Cornell, to the work of computer hackers, “infiltrating the publishing establishment” as a “form of literary subversion” — more syncretism than adaptation.

The multilayered references used by such authors challenge notions of authenticity in terms of what is local and global, and delves more into the fantasy realm of storytelling.

Of course the adaptation of references beyond the local is never a one-way endeavor. A global interest in modern Arabic literature has increased in recent years. Most English-language academic syllabuses are still obsessed with European and American canonical authors, but the internet and increasing diaspora communities are introducing Arab writers and filmmakers into the mix.

A new generation of Arab storytellers, some of whom have arisen from blogging and film writing, are playing with creative notions of adaptation, for example Muhammed Aladdin (Ingeel Adam (The Gospel According to Adam), 2006), Rajaa Alsanea (Banat al-Riyadh (Girls of Riyadh), 2005), and Alaidy. Some are bilingual, and their subversion of traditional forms of narrative structure is changing the ways in which Arabic literature is read and understood.

Sadly adapted novels such as those in The People’s Entertainment are not on the radar of most contemporary scholars and publishers, Selim says. She says there was a moment when she wondered if her interest in them was a bizarre fascination, but when she gave a few of the stories to her mother, she also loved them.

She also tells us that more than 60 percent of this periodical, published in Cairo between 1904 and 1911, has disappeared from Dar al-Kutub since she started her research in 2003.

Meanwhile, in downtown Cairo last month, a few hundred young people gathered for EGYcon — a localized version of Japanese Cosplay, in which fictional characters are re-enacted. This is part of a phenomenon of global youth culture, but was also adapted to the local context, generating self-reflection and challenging norms through gender bending and experimentation.

The fact that translation and adaptation are, as Selim says, “the most basic, if largely invisible, mechanisms in the production of new genres, devices and motifs across literary cultures,” is evident not only in the circulation of fiction, but also in wider popular culture.

Samah Selim’s talk can be watched here. She is also speaking at downtown Cairo’s Rawabet today, March 6, at 10.30 am, on Text and Context: Translating in a State of Emergency, as part of the The Only Thing Worth Globalizing is Dissent conference organized by Mona Baker, Yasmin El Rifae and Mada Masr.

http://www.madamasr.com/sections/culture/who-do-stories-belong

Although it has a long and varied history, adaptation is a contentious issue today amid copyright and publishing norms. Selim suggests that the Arabic novel has lost an organic fluidity with the development of a literary canon and intellectual ownership.

Many have accused Ahmad Mourad of reproducing characters from Naguib Mahfouz in his novel 1919 (2014), and borrowing from Peter Burger’s New Zealand film The Tattoist (2007) — which, Selim notes, mimicked a number of other films before it — in writing Al-Fil al-Azraq (The Blue Elephant, 2012). There has also been much discussion about the influence of Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club (1996) on Ahmed Alaidy’s An takun Abbas al-Abd (Being Abbas al-Abd, 2003).

Going back in time, during the late 19th and early 20th century Nahda (Arab renaissance), critics questioned whether the Arabic novel itself was merely a mimicking of a European genre.

But the novel’s journey into Arabic was actually “clandestine, meandering and mischievous,” Selim argued in her fascinating lecture for the AUC’s Center for Translation Studies, “The People’s Entertainment: Translation, Adaptation and the Novel in Egypt.”

Established by Khalil Sadiq in 1904 and published until 1911, The People’s Entertainment included at least 80 novels and short stories. Selim says around 12 were originals, 13 were close translations of foreign-language novels, 27 were adaptations citing an original author, and the remainder are not attributed, but loosely based on French or English fiction.

Certain adaption processes make the novel an “adaptable, anarchic and popular genre,” Selim said.

She cited Arsène Lupin, French writer Maurice Leblanc’s fictional character, whose adaptation in Arabic hasn’t been merely a “copying by the subaltern,” but a way of drawing on older forms of local popular knowledge. Similarly, the first Arabic version of Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) was published in 1838 anonymously and followed by a host of other adaptations.

Imitation and adaptation were the norm everywhere before 18th-century Romanticism emerged, Selim points out, along with the parallel emergence of nationalism in Europe.

The People’s Entertainment had a large readership and was written by journalists, lawyers and men of letters. Its advertisements indicate an audience of largely middle-class professionals.

Fiction was hugely popular. Between 1858 and 1873, 30 new journals dedicated to publishing fiction in Egypt and Syria were established, along with numerous newspapers. The state-owned Al-Ahram newspaper, which started publishing in 1875, also regularly published translated or adapted fiction in its pages.

Discussion around Arabization, Egyptianization, and creative adaptation were prevalent during this period, with texts commonly presented as “authored by,” “rendered by” or “from the pen of” in pieces seen more as a “textual voyage” than a fixed moment of ownership, according to Selim.

She explains that some 20th-century Arab authors even published their own original stories as translations, as the genre was so popular.

Selim challenges the notion this was pure obsession with the “foreign.”

Firstly, the foreign novels selected for adaptation often contained an implicit critique of global modernity and predatory capitalism, which coincided with the catastrophic 1907 stock-market crash in Egypt. In this way, European and American cities, particularly Paris, were stripped of their specificity and came to symbolize the global system and a cultural voyage beyond merely the self and the other.

Secondly, Lebanese author Jurji Zaydan drew parallels between the European novels of the nineteenth century and oral Arab storytelling traditions, such as The Thousand and One Nights.

This form of domestic critique and self-reflection was not as concerned with the colonial discourse of power as the state project was. The fascination with adapted novels confused some critics and scholars, for example when state-supported novels such as Mohamed Hussein Haykal’s Zaynab: Manazir waaakhlaq rifiyyah (Zaynab: Country Scenes and Morals, 1913), were not as widely read as such “authentic,” national novels were expected to be.

Adaptation has always been part of the development of new genres, Selim claims. And although the power relations in the colonial and post-colonial context problematize translations and adaptations like those in The People’s Entertainment, and might prejudice people against them, they can also be used to subvert these power relations by destabilizing the original.

In a theory of mistranslation developed in The Translators of the 1001 Nights(1936), Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges emphasizes the “importance of the displacements that occur when one goes from original to translation, and how these displacements create the potential for new and unexpected meanings.”

What some have labeled textual disruption and mimicry, referring to authors like Ahmed Alaidy, has been compared by Tarek al-Ariss, associate professor of Arabic literature at Cornell, to the work of computer hackers, “infiltrating the publishing establishment” as a “form of literary subversion” — more syncretism than adaptation.

The multilayered references used by such authors challenge notions of authenticity in terms of what is local and global, and delves more into the fantasy realm of storytelling.

Of course the adaptation of references beyond the local is never a one-way endeavor. A global interest in modern Arabic literature has increased in recent years. Most English-language academic syllabuses are still obsessed with European and American canonical authors, but the internet and increasing diaspora communities are introducing Arab writers and filmmakers into the mix.

A new generation of Arab storytellers, some of whom have arisen from blogging and film writing, are playing with creative notions of adaptation, for example Muhammed Aladdin (Ingeel Adam (The Gospel According to Adam), 2006), Rajaa Alsanea (Banat al-Riyadh (Girls of Riyadh), 2005), and Alaidy. Some are bilingual, and their subversion of traditional forms of narrative structure is changing the ways in which Arabic literature is read and understood.

Sadly adapted novels such as those in The People’s Entertainment are not on the radar of most contemporary scholars and publishers, Selim says. She says there was a moment when she wondered if her interest in them was a bizarre fascination, but when she gave a few of the stories to her mother, she also loved them.

She also tells us that more than 60 percent of this periodical, published in Cairo between 1904 and 1911, has disappeared from Dar al-Kutub since she started her research in 2003.

Meanwhile, in downtown Cairo last month, a few hundred young people gathered for EGYcon — a localized version of Japanese Cosplay, in which fictional characters are re-enacted. This is part of a phenomenon of global youth culture, but was also adapted to the local context, generating self-reflection and challenging norms through gender bending and experimentation.

The fact that translation and adaptation are, as Selim says, “the most basic, if largely invisible, mechanisms in the production of new genres, devices and motifs across literary cultures,” is evident not only in the circulation of fiction, but also in wider popular culture.

Samah Selim’s talk can be watched here. She is also speaking at downtown Cairo’s Rawabet today, March 6, at 10.30 am, on Text and Context: Translating in a State of Emergency, as part of the The Only Thing Worth Globalizing is Dissent conference organized by Mona Baker, Yasmin El Rifae and Mada Masr.

http://www.madamasr.com/sections/culture/who-do-stories-belong