Arab Comics: Fit for Academic Exploration

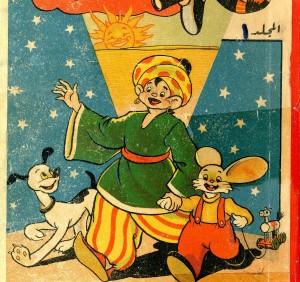

Comic magazines Samir, Lulu and Mickey Geeb (Pocket-sized Mickey) and Arabic translations of Tintin, Superman and Asterix and Obelix have been read and loved by generations of Arabs. Editorial cartoons are fundamental parts of every daily newspaper. But comic art remains an often unexamined and under-supported part of Arab artistic effort.

A new initiative is intent on changing that.

In September, the American University in Beirut (AUB) began a new academic program focused entirely on the study, archiving and promotion of Arab comic art. Named after its biggest donor, the Mu’taz and Rada Sawwaf Arabic Comics Initiative will also hold an annual conference to promote the artistic field and sponsor the Mahmoud Kahil Awards to highlight emerging creative talent in the field.

Mu’taz Sawwaf and the initiative’s founding director, Lina Ghaibeh are both published comic artists as well as avid comic book collectors. Early on in his career as a comic artist, Sawwaf decided it wasn’t a realistic career choice. He pursued architecture and engineering instead. Now, he hopes that the program will aid the careers of future comic artists, providing them with opportunities that he and other artists were denied.

“Look at the first generation of Arab masters in cartoons and comics, the Mahmoud Kahils, Pierre Sadek, and the Bahjouris of the Arab world,” he says. “They were left cash [strapped], yet now their art is worth millions, unfortunately mostly after their [deaths]. I hope that within five to six years, we will be able to encourage young artists to pursue a career in [comic] art and make a comfortable living.”

With the new program, the American University of Beirut joins a few other institutions offering degrees and supporting research on comic art, including the University of Florida, the University of Toronto and the University of Dundee, in Scotland.

“The Arab world is a wonderfully rich area, with a whole cultural heritage that has not been explored and deserves to be studied,” Ghaibeh says. “There have been [extensive] studies of comics in the U.S. and Europe, even the Far East; yet Arab comics have not been touched. “

Through the program, researchers will also have access to professional studio spaces, advanced digital imaging labs and university research centers.

Dating back to the early 1920s, Arab comic art provides fascinating insight into political propaganda and orientalism as well as cross-cultural influences.

“Comic art is a very rich form of Arab cultural heritage and mass media,” Ghaibeh adds. “There is a massive amount of editorial cartoons that tell you the history of the region.”

For example, some of the first unique Lebanese comics, Zarzour in the 1950s and Bissat El Reeh in 1962, depicted freedom fighters as superheroes and had heavily political themes for their target audience of children, according to a NOW Lebanon report.

The very first original Arab comic, Al Awlad, was published in Egypt in 1923. “The original creations were trying to tell stories for a younger audience that had an Arab point of origin,” says an Arab comics scholar, Nadim Damluji. “This is not to say they weren’t political, as Hussein Bicar, the founder of Sindbad, was a member of the Society of Post-Orientalist; he was very conscious of the power of the medium and how it could be used to further pan-Arab ideas.”

Cross-cultural influences are evident in Katkot, a comic magazine published in Lebanon in 1946, which contained Arabic translations of The Adventures of Tintin alongside original Arabic stories.

Egypt dominated the comic publishing industry for many years, publishing magazines such as Samir in 1952. Lebanon replaced Egypt in the 1960s as the largest hub of comic production, according to Lebanese comic artist George Khoury. With a relatively high freedom of expression compared to the rest of the Arab world today, Lebanon appears to have become the epicenter of comics production.

The lack of statistics on readership of comic art in the Arab world is irrelevant, says writer Jonathan Guyer of Oum Cartoon, as the genre’s popularity is evident on the streets.

“Every newspaper in Egypt publishes cartoons, every newsstand in Cairo sells new comics,” he says. The genre has influenced other mediums such as advertising, graphic design and street art, he adds. According to Guyer, many artists such as Egypt’s Ganzeer grew up reading Arab comics and cite them as profoundly influential.

“I think the art that has been produced post-2000 is as good if not better than similar art produced in the bigger markets of the United States, Europe and Japan,” says Damluji. Despite the quality of Arabic comics, he says, “they are often left out of conversations of the medium in the Western academy.”

While several blogs showcase the history and diversity of Arab comics, such as Majalat, Qantara and Arab Lit, the Sawwaf initiative aims at becoming the largest digital and physical resource of Arab comics in the world.

By including Ghaibeh’s database of over 4,000 Arab comics, the university’s database of several hundred issues and a future in-kind gift of several thousand issues from Sawwaf’s personal collection.

The initiative’s library will include illustrated books from the early 20th century as well as more recent productions like Samandal, an award-winning experimental Lebanese quarterly launched in 2008 and available online via a Creative Commons license.

Another important addition to the library is Tok-Tok, a self-published Egyptian quarterly started in 2011 by a group of young graphic artists.

Like Samandal, Tok-Tok’s issues are also available online to cater to their large digital audience and also possibly to avoid state censorship, an issue that should not be taken lightly in the Arab World, considering the number of arrests and attacks on artists in the region. The Egyptian comic book Metro was banned in 2008 and its author Magdy El Shafee was convicted of offending public decency. Fellow Egyptian Doaa El Adl faced charges of blasphemy in 2012 for her heavily political caricatures. Syrian dissident cartoonist Ali Farzat was kidnapped and severely beaten by pro-Assad forces in 2011.

Beirut-based illustrator Fouad Mezher, whose comic series The Educator ran from 2007 to 2010, studied under Ghaibeh at AUB and believes the program will help promote the medium in the Arab world.

“With mainstream comics becoming a dominating force in pop culture, it’s preferable that the more subversive comics can be given a longer lifespan and can pertain to a real discussion through preservation in an academic environment,” he says.

Alfred Badr, a Beirut-based illustrator and graffiti artist, is excited to be able to study comics at AUB instead of having to travel abroad.

“I was looking into joining any course that would strengthen my comic drawing skills, so it would be superb to be able to do this in Beirut and meet fellow local artists,” he says. “I’m very excited and hope to be able to attend the program’s events.”

The AUB has put itself in a position to really shake up the way we talk about comics,” says Damluji. “In the last few years the academic world has begun to realize that the study of comics is a rich discipline that has a lot of work to be done within it. All in all, it is a good time to be studying comics in the Middle East.”

Further information about Arab comics, including online comic books, awards and articles related to Arab comics can be found on the AUB’s online resource.