The Case of the Arabic Noirs

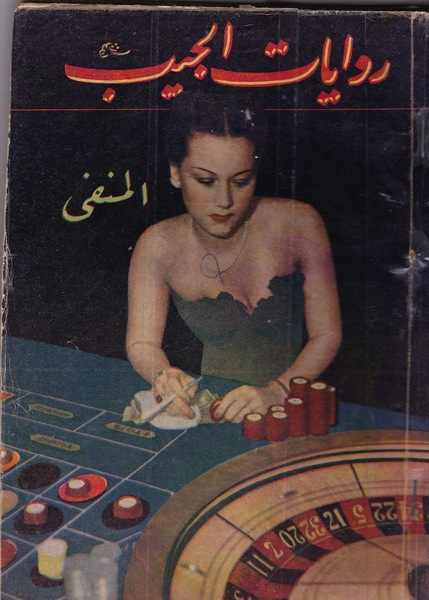

Pocket Novels: The Exile, J. Kessel, 1940. “A Novel of Human Untruths, about a Russian woman and her princesses, in exile, from the pen of the great French writer J. Kissel,” presumably the French novelist and journalist Joseph Kessel (1898-1979)

August 20, 2014 | by Jonathan Guyer

Cairo: the metal detector beeps. The security man wears a crisp white uniform. He nods and leans back in his chair. The lobby’s red oriental carpet, so worn it’s barely red, leads upstairs to the hotel tavern. Enter the glass doors, where a cat in a smart bow tie and vest reaches for a lonely bottle behind the bar. He takes his time; he’s been polishing glasses at the Windsor Hotel for thirty-eight years. Out the window, a motorcycle speeds through the dark alley. In 1893, this joint was ritzy—home to the royal baths, steps from the original Cairo Opera House. Tonight it’s dingy enough that Philip Marlowe might come here to tip a few back after clobbering some hoods. A fine joint in which to pore over pulp from the secondhand book market down the street.

It’s tempting to ponder the relevance of crime novels in contemporary Egypt. The 2011 revolution began on National Police Day as a revolt against the fuzz. When President Hosni Mubarak breezed off eighteen days later, the police dusted, too, leaving behind a Wild West. Gun sales skyrocketed, matched by holdups and carjackings. In the following two years, thugs ran Cairo’s streets. Ever since General Abdel-Fattah Al-Sisi ousted former President Mohammed Morsi last summer, the coppers have been back in full force. White uniformed police operate checkpoints littered throughout the capital like discarded Coke cans. Cabbies are so scared that they’ve started wearing seat belts. And now, as authorities attempt to restore law and order, the crime genre is making a comeback.

Pulp emerged at the turn of the twentieth century. In the U.S., the twenties and thirties were the heyday of gumshoe thrillers, as Chandler and Hammett wrote detective stories for Black Mask. At the same time, Egyptian writers and translators produced thousands of unauthorized paperbacks, capped off with covers as lurid as their Western cousins’. In Cairo, each publishing house boasted hundreds of serials. Double Crime, for instance, a 1967 Arabic translation of the best-selling American novelist Norman Daniels, was number 420 in one publisher’s World Stories imprint. From Alfred Hitchcock and Charade to works of forgotten French and British novelists, anything and everything was translated into Arabic. The mass-market trend continued into the seventies, when sci-fi, Westerns, and spy novels began to outsell the tall tales of dizzying, melodramatic dames.

The golden age of illicit crime fiction translation—from the 1890s through the 1960s—corresponds to the construction of the Egyptian nation, from colonial rule and monarchy to President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s nationalization project. It’s the period when the Egyptian novel was canonized with stories of national consensus and the patriarchy: quite different than hotheaded genre fiction.

These translated thrillers captivated Egyptian readers in part because they shined a torch on the contested legal system of colonialism. The plots would be familiar to those who watch The Wire—inefficient courts, bumbling officers, the law’s futility in the face of crime. A classic example is Tawfik Al-Hakim’s Diary of a Country Prosecutor, a 1947 novel that’s part biographical, part hard-boiled, with a dash of bitters thrown in. The prosecutor waxes cynical about the legal institutions of British colonialism. In a satirical courthouse scene, Al-Hakim demonstrates the law’s worthlessness in the Nile Delta, where rural Egyptians are “required to submit to a modern legal system imported from abroad.” As in James M. Cain’s Double Indemnity, the law here can be fudged; the real disputes are settled outside of court.

“These novels form a tradition of legal muckraking,” writes Elliott Colla, chair of Georgetown’s Department of Arabic and Islamic Studies and the author of a new thriller, Baghdad Central. “Writing fiction about impolite or contentious social issues became an alternative way of addressing problems normally resolved through legal deliberation and action.” The stories of prosecutors and shamuses portrayed the ambiguity of law and order. All crime novels are political.

From the turn of the nineteenth century to the 1940s, Egyptian readers “had been accustomed to a steady stream of detective pulp fiction,” writes Colla. The remains of that vast canon are still strewn across the country. On a recent trip to Alexandria, I watched a hardened bookseller, a cigarette dangling from his lip, unload three grimy suitcases packed with English thrillers: The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, The Kiss-off, Casino Royale, House Dick, and dozens more. At the next stall, a table offered Arabic titles, with monikers like The Corpse, Floozy from Paris, Secret of Radium, and Lust for Murder. Each cover is more craven than the last: gun-slinging babes, gambling sexpots, smoking revolvers. The back covers offer red-hot teasers. “A police story of fantastic events … ” “The life of a French prostitute … ”

It’s too soon to speak of the Arabic noir’s resurgence, but there are clues. Ahmed Mourad’s 2007 novel Vertigo is a fine place to start. Mourad snapped photos for former President Hosni Mubarak; like Egyptian thriller writers of the forties, Mourad comes from an elite perch and knowingly comments on law and order in a lawless place, reviving tropes long beloved by Egyptian readers. (In reviewing Vertigo, one writer falsely called the thriller “a genre largely unknown in the Arab world.” He must not have visited Cairo’s book markets.) Vertigo begins in the rotating top-floor restaurant of the same name, situated in a posh Nile hotel. The protagonist, a down-and-out wedding photographer named Ahmed, sneaks a cigarette on the balcony as two heavyweights hold a private powwow at the bar. Suddenly, hatchet men break in and pump the goons with metal. The ensuing bloodbath leaves a pile of stiffs, including the house pianist, Ahmed’s best pal. This is a grimy look at the underbelly of Mubarak’s crony capitalism—the book is a best seller and has been translated to English.

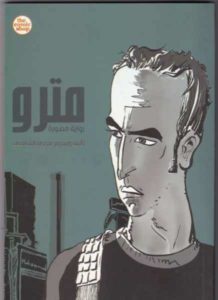

Another modern-day equivalent of pulp is the graphic novel—an emerging medium that illustrates the divey corners that sleuths and skirts frequented a half century ago. Metro, by Magdy El-Shafee, is known as the original Arabic adult comic book, and it’s a kind of Cairo noir: on the first page, a beleaguered young computer programmer decides to rob a bank. When it was first published in 2007, Egyptian authorities seized all copies from the publisher, though the reason remains a mystery. Was it the narrator’s harsh antiregime attitude, his use of nudity and expletives, or the publisher’s activist reputation? The book was republished in Cairo after Hosni Mubarak took a fall, but it’s still hard to find in Arabic. (It’s on sale worldwide in translation.)

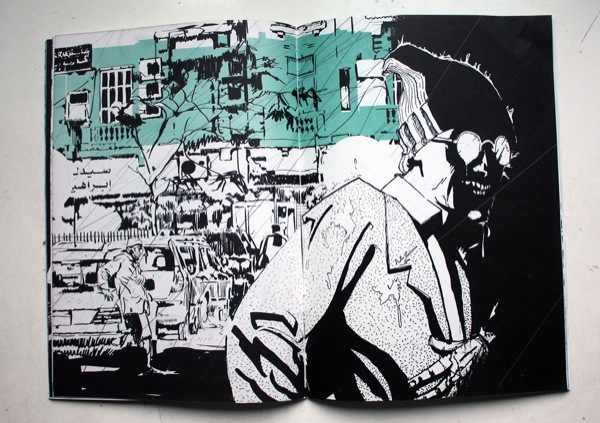

Whatever the reason for the comic’s censorship, its notoriety provoked other young artists to engage with noir aesthetics in telling contemporary stories of depravity. Ganzeer, the pseudonym of a thirty-two-year-old graphic artist whose art installations and graffiti are landmarks in Cairo and elsewhere, is inspired by Metro’s antihero. “Of course you could relate to someone opposing the government, opposing the police, more so than you can relate to this idea of a noble police officer who has to solve crimes for the greater good,” Ganzeer has said. This is the common thread between the new graphic novels and noirs of old: don’t trust the law.

In May, Ganzeer decided to skip town. A jingoistic Egyptian TV host put a finger on the artist. On live television, that gangster TV anchor disclosed Ganzeer’s real name and aired his photo, in retribution for antiregime graffiti. Ganzeer is now in New York, having drifted from one noir city to another.

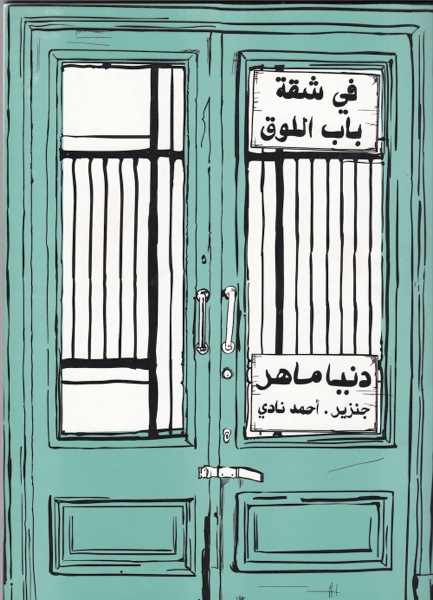

Ganzeer’s latest publication is a hard-boiled graphic novella written by Donia Maher, a Cairo-based writer, entitled The Apartment in Bab El-Louk. Ganzeer elegantly laid out the text, the scattered rantings of an agoraphobic misanthrope, more poetry than prose—alongside images of the gritty downtown flat. You’re forced to listen to the anonymous narrator, screaming at unwanted visitors, neighbors and maids who knock on the door of the cramped apartment. Hitchcock might have conjured up such a neurotic character, a dark face peeping out the window at a quarrel on the street below. “You’ll be scared, even though you’ve locked the door,” says the narrator, speaking with brevity that portends doom.

The last eight pages of this “fabulous noir poem,” as its been called, feature a comic by Ahmed Nady. He’s an insurgent graffiti artist and illustrator of grotesque political caricature, the perfect guy to draw a shakedown at the hands of corrupt cops. In his comic, we learn that the reclusive narrator has been murdered. The cops bust into the joint. But they pinch a patsy, an innocent neighbor, rather than the real culprit.

“The cops are not the heroes in this story … That’s not the way things roll in Cairo. You don’t have an investigator; you don’t have a private eye, or whatever. You’re totally on your own,” Ganzeer said in April, in his Cairo studio, beside a floor-to-ceiling bookshelf of English and Arabic comics. He emphasized the pervasive antipolice violence that climaxed during January 2011 uprising: “People went and burned down every single police station.”

From the Semiramis Hotel’s lobby, a two-minute waltz from Tahrir Square, Cairo itself seems like a dime novel. The Semiramis itself has been ransacked by toughs several times since the revolution, and last year, the hotel chefs brandished kitchen knifes to scare off troublemakers. Simply reading the newspaper stirs up familiar noir themes. Headlines provide grist for whole novels: “Egyptian police captain sentenced to death for murder-robbery.” Or “Egypt policeman killed defusing bomb near president palace.” And “Policeman shot dead while rescuing girl from kidnappers.” And last month, a new soap opera on police corruption was banned. In Cairo, it seems, life imitates pulp. Time to rent a room at the Windsor and start typing.

Jonathan Guyer is senior editor of the Cairo Review of Global Affairs. He blogs at Oum Cartoon and tweets @mideastXmidwest.

http://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2014/08/20/the-case-of-the-arabic-noirs/

Jonathan Guyer is senior editor of the Cairo Review of Global Affairs. He blogs at Oum Cartoon and tweets @mideastXmidwest.

http://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2014/08/20/the-case-of-the-arabic-noirs/