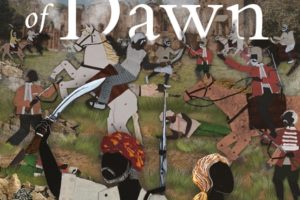

This translation of a historical novel asks whether the writer and the translator are joint authors

Ali Khan Mahmudabad’s translation from the Urdu of Khan Mahboob Tarzi’s ‘The Break of Dawn’ is as much the translator’s mission as the writer’s story.

The Break of Dawn, by Khan Mahboob Tarzi, which has been translated from the Urdu by Ali Khan Mahmudabad, welcomes readers with a preface that takes them through the origins of this translation. In it, Khan, the translator, talks of enquiring about the roots of his own ancestors, the cause of the revolution of 1857, and why this became an important presence in his own life.

The erstwhile royal family of Mahmudabad – to which the translator belongs – had played a pivotal role in the revolution, which ultimately led to Mahmudabad Qila, the seat of the family, being razed to the ground. What exists today was rebuilt on those ruins.

Muqueem Ud-Daula Raja Nawab Ali Khan, who died in the war of 1857 – the ancestor whose history the translator seeks to uncover – is a pivotal character in the book. Even though the main narrative takes us through the tumultuous love affair of Riyaz and Alice, it remains incomplete without the translator and his historical background. So, the translation turns into a homage of sorts to the ancestors of the translator who fought in the mutiny and remain as a spectral presence throughout the book.

Who holds the power?

In an unintendedly ironic turn of events, this translated version in English may also revive the image of the author, Khan Mahboob Tarzi. Tarzi, as the translator reminds us, was a struggling author and did not receive recognition or money for his art.

The footnote plays a dual role in this book. While translating all the original footnotes, Khan adds his own to supplement the translation, creating an additional commentary in the process on the historical essence of this novel. Tarzi, in fact, mines historical references to not only root the story in its time, but also to allow us to work out how we can actually look at this war.

That is not to say that the fictional story of Alice and Riyaz is any less interesting. In fact, the enhancement of the setting makes it all the more of a “swashbuckling” adventure, as the translator puts it here.

But if we are to argue that in a translation it is the translator who wields the power, since readers get the “original” work only through the mediation of the translator, all such books by definition belong equally to both the author and the translator. And because, in this case, Khan is personally invested in the history of his own world, he seems to be present in the battles and even in the qila of Mahmudabad.

With this investment, it appears that the power of the narrative shifts in the translated version, which becomes at least as much Khan’s as Tarzi’s. In his introduction, Khan provides close directions for reading the book, making it clear that the translator’s is going to be a constant presence in the text.

Intersectional translation

The close directions on how to read the book laid out in the introduction pretty much tells us how closely the translator will slip in and out of the narrative. It becomes acutely impossible to read the novel without being aware of the fact that it was Khan’s quest for Muqueem Ud- Daula’s history that gave us the opportunity to read Tarzi in the first place.

Who is the author of this book in our hands then? Roland Barthes ends his famous essay, “Death of the Author” with this line: “…the birth of the reader must be ransomed by the death of the author.” But how does the reader ignore the motivation of the translator in this case, especially as Khan’s footprint is constantly felt in the explanations, footnotes and, often, invisible commentary accompanying the text?

In fact, one can go so far as to say the translator here is not merely a placeholder for the author, not just the medium for the author to speak in a new language. This in turn makes the question of authenticity moot as well. You just have to trust the translator’s version of the story, for he is determined not to be transparent.

But is it a good translation? Perhaps only those who can – and do – read both the Urdu novel and the English one can answer that. However, the fascinating quest of family history implicit in the translation and the actual love story of Riyaz and Alice in the novel make for an unusual intersection between romance and nationalistic fervour on the one hand and the translator’s personal journey on the other. Indeed, one can even hazard the guess that Tarzi would have enjoyed this mash-up.