Why Did an Israeli Publisher Release a Book of Translated Arabic Essays Without Consent?

The decision to translate and publish the works of dozens of women authors, without their involvement or approval, points to unethical publishing practices.

Hakim Bishara, Hyperallergic

September 13, 2018

TEL AVIV — A new book released by the Israeli publisher Resling Books is under fire for publishing a collection of stories by leading Arab women writers without their permission. Editor and translator of the anthology, Dr. Alon Fragman, coordinator of Arabic Language Studies at Ben Gurion University of the Negev, writes in his introduction that the purpose of the book is to surface the texts of writers “whose voices have been silenced for years.” Now those same writers are decrying the violation of their copyrights through the inclusion of their works in this book, without their consent.

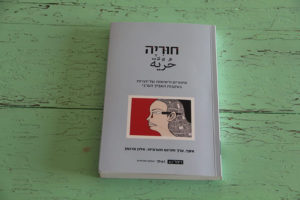

Titled Huriya (a transcription of the Arabic word for Freedom), the book gathers stories by 45 women writers from 20 predominantly Arabic-speaking countries, stretching from the Persian Gulf across North Africa. Among those are renowned writers such as Farah El-Tunisi (Tunisia), Ahlam Mosteghanemi (Algeria), Fatma El-Zahra’a Ahmad (Somalia), and Nabahat Zine (Algeria). The anthology treats the subject of freedom by showcasing works written in the aftermath of the Arab Spring revolutions which, according to Fragman has brought about a “literary spring” as well.

Khulud Khamis, a writer based in the city of Haifa in northern Israel, was invited by the publisher to participate in the book’s launch event planned for October. “While leafing through the book, I noticed the large number of writers from across the Arab world and I suspected that the writers were not asked for permission for the translation and publication of their works,” Khamis tells the Arabic online magazine Fusha. Her suspicion was validated after she contacted some of the writers. Khamis has canceled her participation in the event and posted the news on social media, calling her followers to alert the other writers about the unauthorized publication of their works. A torrent of condemnations by the writers has followed.

Najwa Bin Shatwan, a Libyan writer living in Italy, describes the publication, to the website Fusha, as a brazen act of literary theft. Nabahat Zine (Algeria) describes the book as “forced normalization.” The word “normalization” refers to ways organizations, business, and governments act as if there are normal cultural relations between Arab countries and Israel in disregard of its longstanding conflict with Palestinians. This term recurs throughout the writers’ condemnations. Salwa Banna (Palestine) tells Fusha “Those who rob a land won’t find it hard to rob a culture” and describes the book as an attempt to coax Arab writers into a “normalization trap.” Buthaina El-Issa (Kuwait) tells the Palestinian daily Al Ayam: “Of course, they never approached me, because they follow the logic of occupation and expropriation, but still they named the book Freedom. They are shameless.”

Resling Books is held in high regard locally for its catalogue of quality theoretical and political publications. The anthology was published under a new experimental prose section named VASHTI. Last May, the publisher held a “soft launch” event for the book at a Tel Aviv bookstore. Roni Felsen, a local activist who attended the event, told Hyperallergic that Fragman confessed in front of the audience that he did not have permission from the writers to publish their works. Felsen reached out to the publisher on the matter and heard back from Resling’s chief editor, Idan Zivoni. Felsen and the editor Zivoni discussed the matter over the phone.

When the story erupted several days ago, activist Felsen posted Zivoni’s response to her questions about the book and copyright issues on her Facebook page. Below is a translation of Felsen’s post, that is a transcription of the editor’s comment about the anthology. Zivoni said:

This entire story of translation is an issue by itself especially when it’s from Arabic. It’s a different kind of category. When you translate from English, you deal with norms, you have a subject and you ask for rights. We as a publisher do it all the time, and we never publish foreign works without permission. It’s different in the Arab countries, where there are no publishers. Some of these countries have no ties with us [Israel], so there’s no one to contact. In that respect, a symmetry exists. Books by Resling were translated and published there without permission as well…Here we’re not even talking about books, but short stories. In many cases, the writers wouldn’t even be practically allowed give us their permission. These women are putting a call out to the world. This is literature written in body and blood, for some of them it’s a [sic] SOS signal which reaches us thanks to technology….so that we can use it to save lives. Who will hear the cries of these women? In the past, these women could cry out in their kitchen…or in the field, heard only by god maybe? Now somebody is taking these cries, translates them and voices [sic] them here in Israel… It’s important to us that the voices of these women are heard…We take it as their salvation.

Zivoni added that his company is not making any profit from the project, but rather lost money to realize it. Fargman, according to Zivoni, translated the texts for no compensation because he was driven by “a sense of mission.”

“As an Arab female writer, myself, Resling’s response is offensive and patronizing,” Khamis told Hyperallergic. “These writers are not screaming in their kitchens or in the fields, and they are definitely not waiting for the white male savior to ‘save’ them. These are all strong women — activists, human rights defenders, many of whom hold advanced degrees in various fields. Their creative works have been recognized both nationally and internationally. Taking the writers’ words and creations, translating and publishing them into Hebrew — without their knowledge or consent — is the very opposite of ‘saving’ them. They [Resling] have robbed these women of their agency, silenced them, and disregarded their right to make a choice regarding their works,” she added.

Yehouda Shenhav, a professor of sociology at Tel Aviv University, told Hyperallergic, “This is a colonial and misogynistic response, typical of an Israeli left that is disconnected from the Arab world. Publishing works of literature without permission does not build bridges with the Arabs but rather builds walls.” Shenhav, who has also translated books from Arabic to Hebrew, represents another model in the business. In 2014, he founded The Arabic-Hebrew Translators’ Forum, composed of Jewish and Arab members. His latest initiative within that forum is Maktoob, a translation project of Arabic prose and literature into Hebrew for the purpose of bringing those works to the Israeli reader — but never without the writers’ permission. The project, says Shenhav, proves that it is possible to get permission for translations, even from writers in “enemy states.” He adds that it has been a longstanding practice by Israeli academics to translate works from Arabic without any permission, always rationalizing the theft of intellectual property by the assumption that there is no one to talk to on the other side. Fragman, who happens to be a member of the aforementioned forum of translators, is not expected to last there, according to Shenhav. In a statement issued yesterday (Wednesday) by the Middle East Studies Department at Ben Gurion University, the department denounced the book and clarified that Fragman is no longer a member of its staff. It’s an important turn of events given the fact that Fragman still appears on the department’s website as the current coordinator of the Arabic Language Studies at the university. The book also presents Fargaman under that title.

Fragman, by his own account, has done all the translation and editing work by himself without the help of a native Arabic speaker. That, according to Khamis, produced a poor quality of translation that flattens the unique voices of the writers. “The texts deal with issues pertaining to women, their lives, and their worlds. They are intimate and complex. Personally, I don’t think that a white man from a different culture can mediate these experiences without engaging in any form of dialogue with the author.” Khamis brings as an example a poetic description of a “woman strolling down the sidewalks of desire,” in Muntaha El-Eidani’s (Iraq) short story Man, which was reduced in Fragman’s Hebrew translation to a single word — “hooker.” That example is typical of Fragman’s treatment of the texts, claims Khamis. “The Hebrew reader is given a flat shallow text, completely disconnected from the real experiences of Arab women in the Arab world.” This approach, says Shenhav, is indicative of “the orientalism of many of the Israeli translators working in the field.” The great majority of those, including Fragman, started their careers in the intelligence units of the Israeli army, says Shenhav.

This is the second time this year that an Israeli cultural organization is accused of expropriating works from neighboring Arab countries. In July, a Tel Aviv gallery opened a show titled Stolen Arab Art, celebrating its unauthorized use of works by artists Walid Raad (Lebanon) and Wael Shawky (Egypt). Is it a genuine desire to reach out to the Arab neighbors at all costs or is it plain theft? Palestinian writer and translator Eyad Barghouty thinks there is no real thirst in the Israeli public for Arabic culture. “The interested sides are usually orientalists who produce their works from a security-oriented interceptive point of view, believing that culture is a more effective way to gauge the political shifts in the surrounding countries,” he told Hyperallergic. Barghouty calls the new book a “culture crime,” and an act of colonial looting in the dark. “The Israeli orientalists consider the Arab world to be a lawless open space where rules don’t apply. When confronted with criticism over their actions, their reaction takes on a belligerent militaristic tone.” A recent survey showing that less than 10% of Israelis can read or understand Arabic, lends credence to Barghouty’s argument.

Threats of multiple lawsuits are now hovering over Zivoni’s head, since many of the writers announced their intention to take legal action against the publisher. Egyptian writer Intissar Abdul Monaem, reported on her Facebook page that she filed a complaint to the Egyptian Writers’ Union and its Palestinian counterpart. Habib al Sayegh, secretary General of the Arab Writers Union issued a condemnation of the book, calling it an act of “Israeli piracy.” Al Sayegh vowed to pursue the case in legal international forums. But the chances of an actual court case against the publisher are unlikely, given the absence of diplomatic ties between Israel and most of the countries in question. The only way to hold Resling Books accountable is to sue the publisher in an Israeli court, which would mean recognizing the state of Israel and accepting the authority and legitimacy of its legal systems (i.e. “normalization”).

Pouring salt in the wound, it was revealed on Tuesday that the artwork adorning the cover of the book was also taken without permission from its creator, Lebanese cartoonist Hasan Bleibel. Hyperallergic requested comment from the publisher, which remains unanswered as of the posting of this report. Resling Books has pulled the book from its online catalogue without notice.

Why Did an Israeli Publisher Release a Book of Translated Arabic Essays Without Consent?