Picturing Egypt’s Next President

By Jonathan Guyer

Everybody knows who Egypt’s next President will be. Elections are scheduled for May 26th and 27th, almost a year after Mohamed Morsi was ousted in a coup led by the retired general Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi, in what has been painted as a second revolution. With campaigning in overdrive, Sisi met with a delegation of artists on May 12th. According to local news reports, the candidate said that artists are “the heart and soul of the nation,” and its conscience. A nation of some ninety million, however, has many consciences, and no shortage of dissenting creators.

In the three years since the Tahrir Square uprising, art has sprung up everywhere in Cairo. Graffiti is ubiquitous; independent art galleries and collectives are putting up new exhibitions every week. Meanwhile, the state remains a major funder of art. A prime example is the erection of new monuments in public spaces, like the diminutive obelisk in Tahrir Square unveiled in November to honor activists killed during the 2011 uprising, which has since been defaced many times. Even as novelists, poets, and political cartoonists shore up support for Sisi in the media, others are creating art that challenges his authority. With the former defense minister poised to win the country’s top office, will that equation change?

A recent exhibition of caricatures at the Cairo Opera House, hosted by the minister of culture, revealed how official circles approach politics today. Among walls saturated with political cartoons were five hundred illustrations by Egyptian and international artists, and not a single piece criticized the current government. Indeed, caricature is where the red lines are most visible. The art form figures strongly in the Egyptian press, where each paper has its own caricature department. But, since Morsi’s ouster, three major privately owned newspapers have declined political cartoons that were overtly anti-regime. The mainstream media has largely refrained from publishing caricatures of Sisi—a surprise, given the pervasiveness of cartoon attacks on Morsi and on Hosni Mubarak, at least during the final years of his three-decade rule.

Yet creative dissent endures. Recalcitrant cartoonists have found online platforms for their work, and Cairo’s independent art galleries have hosted many radical shows over the past year. “Inventiveness becomes even more crucial because of censorship, and because of the repression of opposing views systematically,” Huda Lutfi, a Cairo-based visual artist, said. Lutfi showed a collection of anti-regime installations at Townhouse Gallery, in downtown Cairo, in December. “The authorities, when I had my exhibition, were more occupied with more immediate things: demonstrations, the Muslim Brothers, and so on. There was no censorship” of the exhibit, she said.

Lutfi was not surprised that Sisi made time to meet with artists during the campaign. “Historically, we’ve seen how situations of crisis bring about a fascist culture,” she said, referring to the authoritarian governments, under Hitler and Stalin, that made strategic alliances with cultural élites to bolster national pride and to crack down on “undesirable” and opposition art.

In Cairo, art has come to be regarded as such a dangerous weapon that, last week, a prominent artist was falsely accused of being a terrorist. The artist, Ganzeer, is one of the few agitators to have rendered Sisi, publishing an inflammatory portrait online. After Ganzeer’s collaboration in a global graffiti campaign against Sisi attracted the attention of the television host Osama Kamal, Kamal wrongly called Ganzeer a member of the Muslim Brotherhood—which was outlawed by the Egyptian state in December. Ganzeer’s tag is known from Cairo to Vienna, but he had previously remained anonymous. Nevertheless, the broadcaster aired a photo of him on the evening news, using his real name as a scare tactic. It was startling because the thirty-two-year-old graphic artist has produced a vitriolic body of work against Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood. “Being anti-Sisi in itself is not a crime,” Ganzeer wroteon his blog. “So I guess Mr. Osama thought it necessary to attach a fictitious crime to my name.”

Social-media outlets have become the primary space for criticism and questioning the government. Some dissent creeps into the cartoons of independent newspapers. “Actually, during these periods, artists become even more inventive, despite censorship,” Lutfi said. But the dangers of crossing the line are real. One illustrator, who regularly posts anti-military caricatures on his Facebook page, declined to give The New Yorker permission to republish his work, saying, “It’s too risky for me.”

At this tense moment, artists are serving as the nation’s conscience. As the Twitter account for Sisi’s campaign, @AlSisiOfficial, declared, “Egypt needs cultural élites, intellectuals, and men of letters to play a very big role during the next phase, guided by national responsibility and submitting to the interests of the country.” Below are images that capture a variety of perspectives on where Egypt is headed.

n this mixed-media montage, Ganzeer replaces Sisi’s head with a television broadcasting a rabbit’s mug. Ganzeer posted this image on his blog, along with an open letter to the television anchor Osama Kamal, demanding that the broadcaster retract false allegations that Ganzeer was a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, considered a terrorist organization by the Egyptian state.

The artist wrote to Kamal, “What you’re doing makes him”—Sisi—“come off as a man who is very afraid of the impact of art. Rather than see us as a threat to the State, critical artists should be seen as a source of information to the State. By paying attention to what we do, perhaps the State can better understand popular grievances and adjust its policies and governance accordingly, rather than invest so many resources into trying to shut us up.”

The hashtag #Vote_for_Pimp exploded on social-media platforms immediately following the announcement, in March, of Sisi’s Presidential candidacy. With harsh anti-protest laws and limited space for dissent in the mainstream media, critics took to Twitter to oppose the former general’s candidacy. This hashtag has also become a graffiti tag across Cairo, a work-around to attack Sisi without using his name.

In this image, which was widely shared on Facebook, Sisi is Simba from “The Lion King,” held up as the prodigal son. Photoshop creations are D.I.Y. political cartoons and the equivalent of online graffiti—agitating art. The ephemeral nature of the meme means that its creators are always responding to the day’s news. When Sisi announced that he was resigning from the military to run for President, for instance, meme creators depicted the retired general in civilian garb, in a variety of incongruous poses—from sipping tea at a popular downtown café to carousing at the seaside resort of Sharm el-Sheikh.

On the cover of this popular children’s comic book, Sisi, at right, stands next to the longtime opposition figure Hamdeen Sabahi, his opponent in the Presidential race. When Sisi appears on the covers of Egyptian magazines, artists depict him glowingly. Note the realistic nature of the retired general’s portrait—there is little exaggeration of his features.

At the “Campaign Headquarters in Support of Sisi,” a young man uses the telephone. “Hello, we need a plumber quickly. We have a pipe of feloul”—remnants of the old regime—“that has burst,” he says.

The twenty-seven-year-old cartoonist, Anwar, drew this for Egypt’s largest-circulation private newspaper, Al-Masry Al-Youm. Rather than caricature Egypt’s most powerful man, Anwar has chosen to critique the structural support and the conditions for his rise. In this cartoon, he pokes fun at the ancien réime, the little men in black suits who have reappeared from the sewer to support the Presidential campaign. This political cartoon represents the furthest that editors have been willing to go in terms of publishing criticism of Sisi.

Even during the time of Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egyptians managed to mock the ruler, according to Abdel Monem Said Aly, the chairman of the corporation that publishes Al-Masry Al-Youm. “During the Nasser period, I mean, the number of jokes about his authoritarianness—it was great,” Said Aly told me. “From how Nasser’s competition was gone to how he is using torture,” Nasser could not avoid comedic treatment. Similar jokes about Sisi, however, have been slow in coming to Said Aly’s newspaper.

A group of Egyptians carries a “Sisi 2014” Presidential poster. Handing it to Mother Egypt, a man says, “Here is our gift to you. May every new year find you safe, Mother of the World.” This cartoon was published in the state’s flagship newspaper a full three months before Sisi announced his bid for the Presidency. Hassan does not caricature Sisi, and uses a popular photograph of the former general out of veneration. This is a typical way in which establishment cartoonists depict the leader—using a Photostat image to avoid cartooning Egypt’s most powerful person.

Taher—a cartoonist, children’s-book author, fine artist, and the art director of the Dar Al-Shorouk publishing house—uses an empty advertisement as a work-around to criticize the Presidential candidates. The billboards of the two Presidential candidates are blank, highlighting how little we know about their prospective plans for the country.

“I am the platform,” the two smiling faces, cartoonish renderings of Egypt’s two Presidential candidates, say. Taher has not yet published any caricatures of Sisi himself, but this image is an example of how cartoonists find work-arounds even as free expression shrinks.

While Hamdeen Sabahi, Sisi’s challenger, has campaigned across the country in order to get out the vote, the former defense minister has been less forthcoming. In fact, Sisi’s campaign has yet to release an official platform, “because releasing the detailed program will be followed by arguments and discussions that we do not have the time to address,” a spokesman told the Al-Hayat newspaper.

Al-Shorouk, a popular independent newspaper, has published cartoons that push the limits; however, the satirist Belal Fadl’s column mocking Sisi’s promotion to field marshal was censored by the paper’s owners. The offending op-ed was published instead by the independent online news site Mada Masr.

This riff on Shepard Fairey’s famous Obama poster was shown earlier this year at the Arab American National Museum, in Dearborn, Michigan. The exhibit, “Creative Dissent,” focussed on the power of visual and symbolic violence amid the Arab world’s ongoing uprisings. This image of Sisi, however, has not appeared anywhere in Egypt.

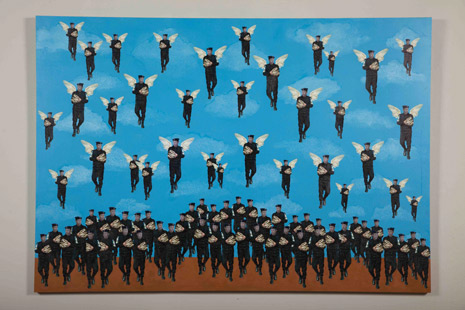

These multimedia works were part of Lutfi’s exhibit, “Cut and Paste,” displayed at Cairo’s Townhouse Gallery. It is a project of archival resistance and memory. Lutfi reappropriates images of police and military conscripts through paintings of boots, cut-out silhouettes, and other modes. “People asked why do I have so many … men in uniform, and I said that they were in my face all the time, because I live downtown and saw them all around me, even before 2011,” Lutfi said.

In the center of the gallery was a dismembered mannequin, with quotations from the Facebook page of the opposition movement April 6, which was founded in 2008, during Mubarak’s rule, and declared illegal by the Egyptian government last month. “We are the generation that gave the police a curfew,” reads one particularly aggressive piece of text on the mutilated bust. For the artist, the disjointed sculpture signifies “all of the repression happening at the moment for the youth of Egypt.”

In January, 2013, a train crashed close to Giza’s Badrashayn station. Nineteen soldiers were killed, and more than a hundred were injured. It’s one of several derailments that has occurred in the past eighteen months. Lutfi seizes the image of uniformed conscripts, each carrying a stack of bread, and challenges the viewer to consider their lives as a way of interrogating the state’s neglect of enlisted men.

Jonathan Guyer is the senior editor of the Cairo Review of Global Affairs. He blogs at Oum Cartoon. On Twitter: @mideastXmidwest.

http://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/picturing-egypts-next-president