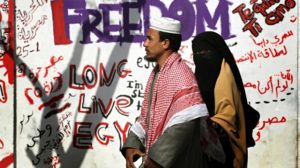

Fascinated by this lexical battleground, Amira Hanafi, an Egyptian-American artist, is travelling across Egypt to create a dictionary of its ill-fated revolution. She is interviewing hundreds of ordinary people about what 160 buzzwords related to the revolution – terms such as “freedom”, “coup”, and even “revolution” – mean to them. The replies will be turned into a book.

Responses to some words highlight Egypt’s huge divisions. Expressions such as “30 June”, the date anti-Morsi protests began, draw positive and negative reactions, depending on the interviewee’s politics. Other words elicit less divided reactions: Hanafi says respondents from all backgrounds have defined the concept of “future” as unpleasant and uncertain. “Pretty much everyone said it’s black, it’s dark,” she adds.

Still more words are revolutionary neologisms such as feloul, which means remnants. It came into common parlance in 2011 to describe the leftovers of the Hosni Mubarak regime – but some of Hanafi’s interviewees now think it should apply to Morsi’s allies, too.

The emerging and still-unfinished work is a snapshot of a country undergoing immense flux, says Hanafi. “The central question of the project is about what has changed [since 2011] – and we’re assessing that through language.”

Mortality is one concept that interviewees say has come closer to home, after three years of bloody street clashes that have led to thousands of deaths. “One guy said he used to think blood meant the blood of animals – and now he says thinks of human blood,” says Hanafi, 35. “A lot of people have said that death used to be something that seemed far away. And now it’s close.”

The changing nature of her project is a symptom of the post-2011 transition. When she dreamed up the dictionary, more than a year ago, Egypt was in a state of heightened public discourse in which people felt comparatively free to talk. Now, after a year-long crackdown in which journalists and activists have been jailed, Egyptians are much warier of expressing their opinions – or of talking to artists asking about revolution.

As a result, Hanafi conducts her interviews in private, and sometimes asks colleagues to interview their friends to avoid her attracting suspicion. “If I was doing this project in 2011, I would have gone down to the street with a recorder and asked the questions there. But now? People won’t answer.”

This has altered the nature of Hanafi’s task. “I had intended [the dictionary] to be a documentation of a conversation that was happening,” says Hanafi. “But now to document the conversation I’ve had to create the conversation – because it’s not happening in public spaces or in the media.”

In Egyptian media, the government and its supporters justify the country’s continuing repression through a nationalist narrative that relies on strict definitions of what it is to be revolutionary – Egyptian and patriotic. In this sense, Hanafi’s dictionary could be construed as subversive because it asks people to unravel words whose meanings are usually only defined by the media. “A number of people have talked about how the media is the source of all this language,” she says. “So this project is really about asking people to repossess the language. What does it mean to them?”

How Egyptians understand the following words

Curfew

“The word ‘curfew’ is really scary. I’m not convinced by anything that lets one person tell another person they have to stay in their house.”

“The curfew had to happen. Yeah, it took away some of my rights but, for me, it was necessary. Like the emergency law.”

“The curfew gave us a bit of a chance to think outside of our daily patterns.”

Harassment “Perhaps in the time of the revolution, ‘harassment’ appeared as an expression or was more widespread. But as an action it has been going on for a long time.”

“Harassment is an old Egyptian thing and all that, but sometimes it’s used systematically as a political tool.”

“The time I felt most safe from harassment was in the days of the sit-ins. I felt like the men and boys were making a kind of wall around the women so that they wouldn’t be bothered or harassed by anyone disrespectful.”

Feloul

“There’s a class of capitalists and investors in Egypt, and when the revolution happened, quite simply, their interests weren’t in line with the revolution. They were named feloul and the word is purely from the Muslim Brotherhood.”

“But it’s not all people who were in the National Democratic party. It’s excessive that you take all of their political rights. No. That’s not right.”

“Linguistically, it means the people who lost the war and chose to escape. But those are Mubarak’s supporters and supporters of the old regime. They’re not running away or anything … they are omnipresent in the state. It’s us who are running away. So it’s not them who are feloul … we are feloul.”

Future

“Before the revolution, the future was unknown and everything was broken … but the country was functioning well. After the revolution, it has got worse.”

“There was a dream for a better and brighter future in the days of the January revolution. But after what happened, and the changes that happened within the state, the future is black.”

“Tomorrow will be black days. Nothing has changed. The economy is collapsing, and people don’t see a problem.”

This article was amended on 18 July 2014 to remove a quote that was not supposed to be included.

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jul/18/egypt-battle-for-language-dictionary-revolution-amira-hanafi