Ethics in the Translation and Interpreting Curriculum

Surveying and Rethinking the Pedagogical Landscape

Report commissioned by the Higher Education Academy

© Mona Baker, 2013

Contents

1. Introduction

1.1. Accountability

1.2. Professional Engagement with Ethics

1.3 Political Conflict

1.4 Technological Advances

2. Ethics in Translator and Interpreter Education and Professional Codes of Practice

3. Incorporating Ethics in the Curriculum

3.1. Conceptual Tools

3.2 Ethics Themes in Translation and Interpreting

3.3 Strategies

3.4 Pedagogical tools

4. Case Study: Introducing Ethics into the Curriculum at Leeds and University of East Anglia

5. Final Remarks and Recommendations

6. Recommended Reading

7. Other References

1. Introduction

The growing pervasiveness of translation and interpreting in all domains of private and public life has been the subject of much commentary in the academic and professional worlds, and explains the unprecedented expansion in the number and range of academic programmes with ‘Translation’ and/or ‘Interpreting’ in their title in recent years. The UK, like other European countries, has witnessed a marked increase in the number of higher education institutions offering such courses under a variety of tiltes, including MA in Translation and Interpreting Studies, MA in Audiovisual Translation, MA in Sign Language Interperting, MA in Conference Interpreting and MA in Literary Translation, among others.

The growth of activity in higher education reflects the fact that translation and interpreting are now increasingly recognised as vital activities and an indispensable part of the professional and social landscape. They have become central to promoting cultural and linguistic diversity and developing multilingual content in global media networks and the audiovisual marketplace. They have also become central to the delivery of institutional agendas in a wide range of settings, including supranational organisations such as the United Nations, the World Bank, the European Commission and the Football Association (FIFA), among others, as well as cultural, judicial, asylum, healthcare and social work services at the national level. These developments, and society’s increased reliance on translators and interpreters, have given rise to new forms of mediation that are subsumed under the term ‘translation’ or ‘interpreting’ and incorported into a wide range of training programmes. Examples include new forms of assistive mediation such as subtitling for the Deaf and hard-of-hearing and audio description for the blind, both of which aim to facilitate access to information and entertainment for sensory impaired members of the community and are now taught either as full MA level degrees in their own right or as part of more generic degrees in Translation Studies.

Such rapid and far reaching changes in work environments have led to increased attention to questions of ethics in the academic literature on translation and interpreting in recent years (Chesterman 1997, Koskinen 2000, Jones 2004, Bermann and Wood 2005, Goodwin 2010, Baker and Maier 2011, Inghilleri 2011, among others). Although, with very few exceptions, this interest has not been reflected in the curricula for training translators and intepreters in any sustained way, the situation is now likely to change rapidly for a number of reasons, the most important of which concern the following: increased accountability; increased engagement by professional translators and interpreters with issues of ethics and a growing willingness among them to exercise moral judgement; greater visibility of translators and interpreters in the international arena as a result of the spread and intensity of violent conflict; and technological advances which have had a major impact on the profession. These are discussed below in some detail.

1.1 Accountability

Accountability is now a central concern in all professions. It requires every professional and every citizen to demonstrate that he or she is cognizant of the impact of their behaviour on others, aware of its legal implications, and prepared to take responsibility for its consequences. While traditionally shielded from the consequences of their decisions by proclaimed values such as impartiality and neutrality which position them outside the interactions they mediate, translators and interpreters are now being held accountable for these consequences in ways that are forcing their educators to introduce more critical thinking and informed decision making into the curriculum. The arrest and trial of Mohamed Yousry in the US in 2005 is a case in point.

Mohamed Yousry, an Arabic translator and interpreter appointed by the court to assist in a terrorism trial, was convicted by a New York jury of aiding and abetting an Egyptian terrorist organisation (U.S. v. Ahmed Abdel Sattar, Lynne Stewart, and Mohamed Yousry, 2005). The charge wasbased on prison rules designed to prevent high-risk inmates from communicating with the outside world. Yousry was held responsible for translating a letter from the defendant (Sheikh Omar Abdel Raman), at the instruction of the attorney (Lynne Stewart), which Stewart later released to the press. He had played no part in devising Stewart’s legal strategy and was not present when she contacted the press. As Hess explains (2012: 24), the ruling against Yousry was paradigm-changing for the interpreting industry. For the first time in US legal history, “an interpreter was held responsible for the actions of an attorney for whom he worked and for the content of the attorney-client conversations which he facilitated”. The case, and others that followed, reminded the profession that interpreters and translators can be held accountable not only for how they translate but also for the content, provenance and circulation of what they translate. [1] If they are to be held accountable in these respects, they must be trained to make ethically informed decisions for which they can knowingly assume responsiblity.

1.2 Professional Engagement with Ethics

Especially outside the domain of literary and religious translation, where engagement with issues of taste and morality is more likely to be found, practising translators and interpreters have traditionally been perceived as apolitical professionals whose priority is to earn a living by serving the needs of their fee paying clients. This is the ‘prototype’ of a professional translator or interpreter that is often presented to students. Indeed, one of the most influential theoretical frameworks that informs translator and interpreter training in many institutions across and beyond Europe, skopos theory (Vermeer 1989/2000, Reiß and Vermeer 1984/2013), assumes that decisions made in the course of translation must be guided by a ‘commission’ from the client (or initiator, or commissioner) who determines what purpose the translated text should serve and what audience it should address (Schäffner 2009: 121). Among other criticisms, this approach has been accused of turning translators and interpreters into “mercenary experts, able to fight under the flag of any purpose able to pay them” (Pym 1996: 338).

In more recent years, however, practising translators and interpreters have begun to challenge this image of their profession by voicing their opinions on a variety of issues and debating the question of ethics explicitly, often to the amazement of clients who continue to think of them as apolitical and unengaged. As one medical translation agency put it in 2010, “[u]nless one’s work involves animal testing or abortion or a similar topic, translators are unlikely to get political about their work”. The agency was quick to note, however, that “the world, it is a-changing”.[2]

The agency in question, Foreign Exchange Translations, decided to conduct a poll following a number of exchanges with translators who refused to take on certain assignments, either because they disagreed strongly with the content of the relevant texts or because of some aspect of the client’s profile. Foreign Exchange Translations framed the poll as follows:

We recently received the following email from a medical translator who has worked for a long-standing device client of ours:

“I’m not sure if you were aware, but there is a boycott in Mexico regarding travel, business, services, etc. related to Arizona and companies based there[3] It has come to my attention that [medical device company] is a company based in Arizona, U.S.A.

I offer my sincerest apologies, but I have to terminate my contribution to this project due to my collaboration with this boycott. My timing is highly unfortunate. I realize this will affect our working relationship. I hope you can understand that had I known this earlier, I would have informed you appropriately.”

It’s not like our team was living under a rock and hadn’t heard of recent events in Arizona but we were nevertheless surprised.

What is your take on this?

Is it the right thing to do to quit work for political reasons? Or should you suck it up and separate translation work from politics.

The poll posed the following question to translators and interpreters who work for Foreign Exchange Translations:

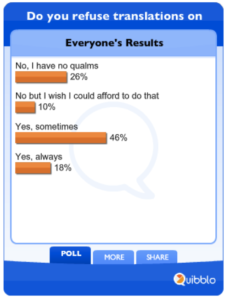

Do you refuse translations on ethical, moral, political, or religious grounds?

It attracted 1571 responses. The results, and translators’ comments on the site, suggest that ethics is now a major concern for the profession. As shown in Figure 1, 18% of respondents chose ‘Yes, always’; 46% chose ‘Yes, sometimes’; 10% chose ‘No, but I wish I could afford to do that’; and only 26% answered ‘No, I have no qualms’.

Figure 1: Full results of poll conducted by Foreign Exchange Translations[4]

This level of engagement by practising translators and interpreters has had an impact on the corporate organisations that employ them. Professional interest in issues of ethics has led at least one translation company to call for a new approach to translator and interpreter training, one that nurtures a “profound understanding of professional ethics” (Bromberg and Jesionowski 2010). Bromberg and Jesionowski are co-designers of an Interpreter Online training programme at Bromberg and Associates, a translation agency located in southeast Michigan.[5]

Such developments in the professional world cannot be ignored by higher education institutions, which should be leading pedagogical innovation rather than lagging behind the professional market.

1.3 Political Conflict

The final decade of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first century have been marked by a number of major wars in which international humanitarian organisations and military forces have been extensively engaged: these include the Balkan wars, the invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq, the war in South Sudan, and more recently European intervention in Libya and Somalia. One feature of this widespread and persistent scenario has been a growing recognition of the involvement and visibility of interpreters and translators in high risk situations of violent conflict that demand the exercise of ethical judgement (Baker 2006, Inghilleri 2010). The impact of at least two related and important developments motivated by these events is beginning to be felt by translator and interpreter educators in many institutions.

First, the international professional associations AIIC (Association Internationale des Interprètes de Conférence) and FIT (Fédération Internationale des Traducteurs) have recently initiated a project in collaboration with RedT, a non-profit organisation, to develop a Conflict Zone Field Guide designed to assist vulnerable interpreters working in war zones. This is a mjaor departure for AIIC, which exercises considerable influence on the content and direction of interpreter training programmes worldwide. As discussed later in this report (section 2), AIIC has traditionally focused on interpreter-client relations within a high profile, predominantly European, elite professional context, rather than ethically charged situations in which interpreters are often vulnerable and likely to confront a wide range of moral dilemmas.

Second, and of more relevance to the current report, the Faculté de traduction et d’interprétation, University of Geneva, one of the oldest and most prestigious institutions involved in training translators and intepreters in the world, now offers virtual as well as face-to-face training to interpreters in crisis zones and is engaged in developing a professional code of ethics specifically for humanitarian interpeters. Its high profile project, InZone,[6] is run in collaboration with humanitarian organisations such as the International Committee of the Red Cross and Médecins sans Frontièrs, as well as the UN High Commissioner for Refugees and the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan. Such partners and settings draw attention to the ethical dimension of the translator’s and interpreter’s work and the impact of their behaviour on vulnerable populations.

These two developments – one at the professional (AIIC/FIT/RedT initiative) and one at the academic level but involving non-academic partners (the InZone Project)– are important milestones on the road to effecting a more sustained engagement with the issue of ethics in translator and interpreter education worldwide.

1.4 Technological Advances

The profession of translation and interpreting, including its various subsidiaries such as audiovisual translation and localisation, is now widely perceived to be under increased threat from new technologies and practices, most importantly machine translation and crowdsourcing. To take crowdsourcing as an example, this is a form of solicited community translation used by large Internet-based groups such as Facebook, Twitter, Wikipedia, and TED, and often considered an effective alternative to machine translation. As evident from the Twitter ‘Translation Agreement’,[7] this growing practice poses a wide range of ethical questions that are rarely addressed in the classroom. The first section of the Agreement alone could be profitably debated from an ethical perspective with translation students, whether they are interested in volunteering for such initiatives or not (bold in original):

Translation Agreement

Terms and conditions do apply. Step 1 of 2.

Overview

Since you’ll be helping out Twitter (thanks again!) we want to let you know our ground rules. Please read the full agreement below before continuing. Here are some of the things you can expect to see:

- We may show you confidential, yet to be released products or features and you must be willing to keep those secret.

- You’ll be volunteering to help out Twitter and will not be paid.

- Twitter owns the rights to the translations you provide. You are giving them to us so that we can use them however we want.

Among other things, Twitter plans to share the translations with the Twitter development community. We want to help make all of the other great Twitter apps, not just Twitter.com, available in your language.

Crowdsourcing is a potentially useful means of reducing the digital divide, but its ethics have been questioned from the perspective of its impact on the profession, as well as the nature of the relationship it configures between the translator and the corporate body that commissions and benefits from the translator’s labour. As the extract from the Twitter ‘Translation Agreement’ above makes clear, this relationship is problematic.

Some translators consider crowdsourcing initiatives such as Twitter’s unethical and damaging to the profession whereas others are motivated to participate for a variety of reasons (McDonough-Dolmaya 2012). An undated petition against crowdsourcing translation initiated by Translators for Ethical Business Practices suggests that many continue to consider the practice unethical and damaging to their status as professionals.[8] Newcomers to the field, including students of translation and interpreting, need to reflect on these developments and assume an ethically-informed position towards them.

The above and other changes that have reconfigured the position of translators and interpreters in society and foregrounded both their vulnerability and their considerable influence on the lives of others call for a different approach to education than has hitherto been adopted. They demand a critical, ethically informed rexamination of what constitutes ethical behaviour in the field of translation and interpreting, and hence the type of training that should ideally be offered to translators and interpreters in higher education.

2. Ethics in Translator and Interpreter Education and Professional Codes of Practice

Translator and interpreter education has traditionally sidestepped the issue of ethics.[9] At most, students are made aware of and encouraged to abide by existing professional codes of ethics, often referred to as codes of conduct or practice by organisations such as AIIC[10] (Association Internationale des Interprètes de Conférence) and the Translation and Interpreting Institute in the UK.[11] Professional codes generally focus on the relationship between the translator or interpreter and their client. They stress the need for impartiality, accuracy and efficiency, these being the traditional cornerstones of professional translation and interpreting, seen from the perspective of the service economy rather than social responsibility or human dignity. As Inghilleri (2009a:20) explains,

Professional codes of ethics that attempt to demarcate the boundaries of utterances and texts from the social, political or historical contexts of their occurrence … emphasize compliance with principles of impartiality while minimizing the ethical challenges that interpreters and translators face in practice, especially where abuses of power or instances of injustice are in evidence. Although the primary duty of interpreters and translators to remain impartial is intended to protect the rights of all parties, there are circumstances when interpreters must weigh the rights of one individual against another to ensure that the objectives of all participants are given equal or adequate space within the interaction. The ability to balance one ethical obligation against another requires moments of genuine ethical insight. There is no guarantee that an individual interpreter or translator will accurately evaluate what is at stake within or beyond a particular encounter just as there is no certainty that a decision they make will produce a positive outcome.What is certain, however, is that interpreters and translators have a central role to play in the inevitable clashes that occur in the moral, social, and often violent, spaces of human interaction.

Figure 2. One of several rotating photos on the homepage of AIIC, stressing neutrality and impartiality [12]

Figure 2. One of several rotating photos on the homepage of AIIC, stressing neutrality and impartiality [12]

4. Impartiality

4.1. Members of the Association shall endeavour to the utmost of their ability to provide a guaranteed faithful rendering of the original text which must he entirely free of their own personal interpretation, opinion or influence;

4.2. The client’s approval must be sought before making any addition or deletion which would seriously alter the original text or interpretation;

4.3. Where an interpreter or translator is working in any matter relating to the law, the client’s statements must be interpreted or translated by the idea communicated without cultural bias in the presentation, by the avoidance of literal translation in the target language or by giving of advice in the source language.

Figure 3. Section on Impartiality in the Code of Practice and Professional Ethics of the Irish Translators’ and Interpreters’ Association, also stressing fidelity and accuracy[13]

This report shares Inghilleri’s concern with the ability of translators and interpreters to balance one ethical obligation against another in authentic contexts of interaction. It therefore argues that training programmes for translators and interpreters, especially in higher education, must encourage students to adopt a more reflective and critical stance towards a wide range of tasks in which they will eventually engage. It should also prepare them to deal with unforeseen ethical dilemmas in a variety of contexts, whether in the professional market or voluntary sector. Such training must recognise that translators and interpreters, like other professionals in all walks of life, have a responsibility towards participants other than the client who pays their fees. In the context of translation and interpreting, these include vulnerable participants such as migrants in the asylum system, members of minority groups such as the Deaf and hard of hearing, and fellow professionals whose livelihood, welfare or reputation might be influenced by the decisions taken by an individual translator or interpreter on specific occasions or over time. The responsibility of translators and interpreters also extends to other human beings who may not be part of their immediate community but can be adversely affected by representational strategies adopted in the translation of literary material or news items, for instance, where the choice of motifs, tropes and lexical variants can exoticise, alienate or demonise (see section 3.2 below). Translator and interpreter training must therefore encourage students to reflect on their positioning rather than refuse to acknowledge that they inevitably occupy a position, to question their own values as well as those of their clients where necessary, and generally to develop an awarenss of the impact of their behaviour on a variety of communities, cultures and individuals and act accordingly.

3. Incorporating Ethics in the Curriculum

Codes of ethics (or practice) adopted by the associations that represent translators and interpreters take as their starting point the need to reassure clients that their members can be trusted to fulfill the expectations and objectives set by whoever commissions and pays them in a totally impartial manner. This may be a necessary discourse to adopt in the service economy for pragmatic reasons. However, in an educational setting, the point of departure has to be a recognition of translation and interpreting as intrinsically ethical activities, in the sense that the act of translation and interpreting simply “cannot proceed without an account (explicit or implicit) of how the encounter with the ‘other’ human being should be conducted” (Goodwin 2010:26). That ‘other’ cannot be reduced to the fee paying client, and training must therefore sensitise students not only to the needs, wishes and rights of the client, but also to the potential impact of their decisions on a wide range of constituencies and participants.

Building ethics into the translation curriculum, then, means opening up a space for critical reflection and training students to examine their values and the consequences of their behaviour, rather than encouraging them to constrain their ethical vision within the bounds of pre-established codes issued by any institution. To maintain a productive and reassuring link with the professional world of translation and interpreting, training must be based on authentic examples of actual translation and interpreting practice and must demonstrate to students that professional translators and interpreters themselves do reflect on ethical issues that arise from their positioning in an ever more challenging moral environment. This is important to challenge the widespread belief that to survive on the market and make a living, and to protect their own ‘integrity’, translators and interpreters have to learn to be apolitical and ‘impartial’ at all times.

These starting points should frame the introduction of ethics into the curriculum. But successful engagement in the classroom requires educators to develop a number of important resources. These include a set of conceptual tools and vocabularly to allow the discussion to proceed; a check list of core themes that raise complex ethical questions and require critical examination in the context of translation and interpreting specifically; a set of activities, whether formally assessed or otherwise, that provide opportunities for students to reflect on and rehearse ethical arguments; a repertoire of potential strategies that may be deployed to prempt or resolve certain types of ethical dilemmas that are likely to arise in the course of translating or interpreting in specific contexts; and a wide range of case studies to underpin training. The case studies have to be varied and must cover various types of activities and encounters that fall under the broad terms of ‘translation’ and ‘interpreting’.

3.1 Conceptual Tools

All higher education training, across the entire spectrum of subject areas but particularly in the humanities, aims to provide students with conceptual tools that allow them to reason critically about a specific area of study or practice. In the current context, such conceptual tools should ideally enable students of translation and interpreting to reflect on the implications of any decision they take – prior to, during, and after the act of translation or interpreting proper. Appropriate conceptual tools are available and can be adapted from a range of disciplines, including the field of applied ethics. They can provide a coherent terminology and a means of reflecting on the pros and cons of particular ways of justifying behaviour, as has been demonstrated in Baker (2011), Gill (2004) and Gill and Constanza Guzmàn (2011), Floros (2011) and Goodwin (2010), among others.

To explore the question ‘what is ethical’ in the context of translation and interpreting, Baker suggests introducing students in the first instance to the broad distinction between ‘deontological’ and ‘teleological’ approaches that is current in much of the literature on ethics in the fields of philosophy and communication studies. She explains this distinction as follows (2011: 276; emphasis in original):

Deontological models define what is ethical by reference to what is right in and of itself, irrespective of consequences, and are rule-based. Kantian ethics … is a good example. A deontological approach would justify an action on the basis of principles such as duty, loyalty or respect for human dignity; hence: ‘I refrain from intervening because it is my duty as a translator to remain impartial’, or ‘I intervene where necessary because it is the duty of a responsible interpreter to empower the deaf participant’. Teleological approaches, on the other hand, define what is ethical by reference to what produces the best results. Utilitarianism … is a teleological theory that is more concerned with consequences than with what is morally right per se. A teleological approach would justify an action on the basis of the envisaged end results; hence: ‘Making a conscious effort [in community interpreting] to remain impartial can help avoid emotional involvement and possible burn-out’ (Hale 2007: 121-122), or ‘I translate as idiomatically as possible because fluent translations receive good reviews’. The distinction between deontological and teleological approaches cuts across … various models of ethics.

Two real life responses to a very similar situation on the part of different interpreters demonstrate the difference between adopting a teleological approach which focuses merely on consequences and a deontological approach which prioritises values such as human dignity irrespective of the immediate or long term impact of a given decision on a participant or the interpreter or translator herself. Both examples are taken from a focus group study conducted by Claudia Angelelli in US hospitals. The study did not engage with issues of ethics but focused instead on the difficulties encountered by interpreters in implementing standards set by healthcare organisations in California. The examples nevertheless make the difference between adopting a teleological or a deontological approach particularly clear.

Let’s say you are a good interpreter, right? And you are interpreting everything that is going on. All of a sudden, I am a nurse, I come in the room and I tell the doctor, “you are giving the patient erythromycin and he is allergic to it. Do you still want to give him that or change it?” Now there is no need for you to interpret that. It has nothing to do with the patient. (Angelelli 2006: 182)

Sometimes when there is an English-speaking patient, the doctor and the nurse do not discuss certain things in front of the patient. They go outside. But when the patient is non-English-speaking, I have been in that situation. I had someone, an older person, come in and he was dying and the two doctors were standing in front of the patient saying “he is going to keep coming here until he dies, until he gets pneumonia and finally…” I can’t translate that for the patient. And I ask the doctors, “Would you like me to translate that?” And they say, “Oh, no. This is among ourselves.” “Then please step outside.” That is what I said. (Angelelli 2006: 183-184)

These examples are quoted by Baker (2011: 282) to argue that a teleological approach minimises the ethical implications of the interpreter’s decision in this context, while a deontological approach suggests that complicity with doctors and nurses in such scenarios means that the interpreter fails to treat the patient with the dignity he or she deserves. She further points out that the same ethical argument(s) can be advanced with respect to the introduction of significant shifts in literary and other types of translation without the knowledge of the author and without alerting the target reader. Here, instead of falling back unthinkingly on prescriptive notions such as accuracy, the conceptual tools deployed allow a more nuanced discussion of the consequences and ethical implications of individual decisions taken in real life contexts that involve a variety of interactants.

The broad distinction between deontological and teleological approaches can provide one type of conceptual map and some vocabulary for reflecting on the moral basis for taking certain decisions rather than others in the context of translation and interpreting. It can help alert students to their own values, and the route(s) by which they decide how they should act in general. But real life contexts can be complex and often raise multiple ethical considerations. Baker draws on an example discussed by Jeff McWhinney, a former Chief Executive of the British Deaf Association, in a keynote presentation at the third annual conference of the International Association for Translation and Intercultural Studies, Melbourne, 2009, to illustrate this point (Baker 2011: 282):

What should a sign language interpreter do … when asked to make a phone call to a sex service on behalf of a deaf client? On the one hand, the interpreter may feel that the sex industry is demeaning and exploitative, and that by supporting it he or she would be doing harm to others. On the other hand, it is possible to argue, in Kantian terms, that the interpreter has a duty to empower the deaf person, who should be able to make his own ethical decisions.

The complexity of such scenarios and the multiple ramifications of decisions made by translators and interpreters reinforce the need to begin a sustained programme for building ethics into the curriculum across higher education institutions, drawing on conceptual tools elaborated in various disciplines, including but not restricted to philosophy and applied ethics. More recent attempts to explore such sources and and offer potentially useful conceptual tools include Gill (2004) and Gill and Constanza Guzmàn (2011), who draw on an ecological model of communication to introduce ethics into the curriculum. An ecological model of education proceeds on the basis of two guiding principles. The first is that “[m]eaning is not fixed but emergent, it is always negotiated, interactive, contextual”. The second is that “[t]he learner who is learning about meaning must engage in the observation of the meta process of communication phenomena. Ecological scholars refer to this as observing observed systems” (Gill and Constanza Guzmàn 2011:101).

Another way of conceptualising ethical issues in the context of training translators has been proposed by Floros (2011), who draws on narrative and norm theories and complements them with the notion of ur-values (i.e. a primordial value such as self-preservation or survival) as a way of elaborating an ethical injunction that reaches beyond stances such as ‘respect for the Other’, ‘Voicing the Other’, and ‘neutrality’. Floros proposes a framework within which students can be sensitised to “the source and target cultures’ mutual need to survive” and are then encouraged through exercises involving polemical texts “to do justice and to weigh ad hoc the best possible way to maintain justice” (Floros 2011: 74), with the recognition that neutrality is impossible and that they will inevitably “oscillate between the poles, sometimes approaching one, sometimes the other. And this happens because they themselves are also guided by the need to survive in this tension” (Floros 2011: 74).

Finally, Goodwin (2010) draws on the heremeneutical model elaborated in George Steiner’s seminal book After Babel (1975/1995), which he considers a bridge between Levinas’s philosophical ethics and the practical issues of translation. This model provides an alternative set of conceptual tools to reveal and redress what Steiner and Goodwin regard as an inherent violence in the act of translation – a violence that makes it imperative for translators (and interpreters) to address the ethical implications of their work. Steiner’s model consists of four ‘movements’: trust, aggression, incorporation and restitution. As Robinson (1998: 97) explains, in the first stage – trust – “the translator … surrenders to the SL text, trusts it to mean something despite its apparent alienness”. In the second stage, aggression, he or she “enters the SL text, driven no longer by passive trust but by the active intention of taking something away, of grabbing up fistfuls of meaning and walking off with them” (Robinson 1998: 97). In the third stage, incorporation, the translator sets out to “facilitate the infection of his or her domestic world by something recognizably other” (Goodwin 2010:33) – to incorporate the Other into his or her own domestic space. The final stage, restitution, is where the translator is ethically obliged to restore the balance that the act of aggression and appropriation has disrupted, to redress the violence enacted on the source text and culture. Robinson (1998: 98) explains the ethical significance of the fourth movement, restitution, as follows:

The translator has invaded the SL and stolen some of its property; now s/he makes restitution by rendering the SL text into a TL that is balanced between the divergent pulls of the SL and TL cultural contexts. … The translator, for Steiner, must be willing to give back to the SL as much as s/he has taken – for example, by transforming the TL through pressure from SL phrasings.

The ethical dimension of translation is therefore expressed in the first and fourth movements – trust and restitution, for “[w]ithout the first movement of ‘radical generosity’, and the final movement of ‘restitution’ translation would quite simply be robbery with violence” (Goodwin 2010: 34).

The current literature then offers several possible sets of conceptual tools that can be deployed in training translators and interpreters to engage with the ethical dimension of the profession. What is needed is an explicit, sustained rationale for building these and/or alternative elements into the curriculum systematically.

3.2 Ethics Themes in Translation and Interpreting

The Inter-Disciplinary Ethics Applied Centre based at the University of Leeds describes its main aim as helping “students, professionals and employees to identify, analyse and respond to the ethical issues they encounter in their disciplines and their working lives”.[14] A screenshot of a page on the website dating back to 2009 and no longer available indicates that the Centre offered (and possibly still offers) training at undergraduate and postgraduate levels in the following disciplines: Biomedical Sciences, Business, Computing, Engineering, Environment, Medicine, Nanotechnology, and Sports Exercise Sciences (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Screenshot of a section of the website of the Inter-Disciplinary Ethics Applied Centre at the University of Leeds, April 2009

Figure 4: Screenshot of a section of the website of the Inter-Disciplinary Ethics Applied Centre at the University of Leeds, April 2009

The University of Leeds has long boasted one of the largest suites of postgraduate programmes in translation and interpreting in the UK: it currently offers an MA in Applied Translation Studies; MA in Conference Interpreting and Translation Studies; MA in Audiovisual Translation Studies; PG Diploma in Applied Translation Studies; and PG Diploma in Conference Interpreting. And yet, Translation and Interpreting do not appear on the list of subjects in which training in ethics is on offer.[15] Section 4 of this document reports on a recent attempt to build ethics in the postgraduate translation and interpreting curriculum at Leeds, but this was largely an individual effort rather than a core institutional commitment. The absence of translation and interpreting from the Centre’s list of subjects within an institution that has a longstanding and highly successful suite of programmes in this field underscores the extent to which the issue of ethics represents a persistent, institutional blindspot. One of the main recommendations of this report will therefore concern the need to garner high level institutional support to build it into the curriculum across UK institutions (see section 5).

For each of the disciplines in which training in ethics is systematically built into the curriculum, the (2009) pages of the Inter-Disciplinary Ethics Applied Centre at the University of Leeds included an introductory page. The one for Medicine read:

Medical ethics deals with matters of moral conduct in medicine; it is about thinking about how one should behave and about what is a morally justifiable course of action. Topics in medical ethics range from the everyday, e.g. consent, to the extraordinary, e.g. separating conjoined twins, to the ground-breaking, e.g. cloning. And they range from the individual, e.g. what is in the best interests of this patient, to the general, e.g. what would be a morally justifiable policy of rationing.

The overview page for the BA in Biomedical Ethics,[16] offered by the same institution, identifies a different set of “matters for moral conduct” in that discipline, including:

- Should smokers and drinkers be placed lower on waiting lists for treatment?

- Can we justify compulsory treatment for some mental illnesses?

- Should patients with advanced dementia be ‘helped to die’?

Translator and interpreter education is yet to identify a set of issues that are particularly important to address from an ethical viewpoint in this field and around which a relevant curriculum may be established. A number of potential areas may be explored briefly here.

First, there is the issue of representational practices and strategies alluded to earlier in this report. Translation is one of the core practices through which any cultural group constructs representations of another. As some scholars have demonstrated, translation can exercise discursive power over ‘Third World’ and other subjects by representing them in ways that cater for the expectations of the target audience (Venuti 1995, 1998), or the agenda of a political lobby (Baker 2010), often with serious consequences for those represented, especially in the context of new information and communication technologies that harness the potential of multi-modality in genres such as televised newscasts (Desjardins 2008) and commercials (Baker, in press) to create powerful stereotypes.

One example that could provide the basis for discussion in the classroom comes from a report published by the BBC on 8 January 2001. The report related to the then widely publicised and heavily contested book The Tiananmen Papers, which is presented as a compilation of selected secret Chinese official documents relating to the 1989 events. The BBC report begins with an editorial comment: “The following are extracts from the secret Chinese official documents on the 1989 Tiananmen Square uprising, published this week as The Tiananmen Papers”. It then goes on to quote long extracts from a meeting between Li Peng and Deng Xiaoping on 25 April 1989. As is common practice in news reporting, BBC does this without alerting the reader to the fact that the English text they are reading is a translation from a (presumed, and in this case contested) Chinese original. More importantly for the purposes of discussing the ethical implications of representational practices in translation, the Chinese speakers are made to speak a very stitled form of English, one that ‘represents’ them as inexorably alien, as this brief extract demonstrates (bold in original):[17]

Meeting between Premier Li Peng and paramount leader Deng Xiaoping, 25 April, 1989:

Li Peng: “The spear is now pointed directly at you and the others of the elder generation of proletarian revolutionaries…”

Deng Xiaoping: “This is no ordinary student movement. A tiny minority is exploiting the students – they want to confuse the people and throw the country into chaos. This is a well-planned plot whose real aim is to reject the Communist Party…”

Translational choices such as “The spear is now pointed directly at you and the others of the elder generation of proletarian revolutionaires” raise serious ethical issues that can be productively debated in the classroom, not from the point of view of accuracy or abstract taxonomies of equivalence, but as reflective of decisions taken during the course of translation that mediate the relationship between readers from different cultures in ways that may impact negatively on one or both communities.

A related issue is the choice of dialects and registers to reflect aspects of characterization in source texts or utterances. This topic has been the subject of much debate in translation studies, though rarely in terms of the ethical implications of allocating a dialect or register to a specific speaker and hence associating him or her and the culture or community they represent with specific values. As Lane-Mercier argues, ‘[w]hat is at stake’ when we render a stretch of text or utterance from one language into another ‘is not so much linguistic difference, as the social and cultural representations of the Other that linguistic difference invariably presupposes’ (1997:46). The choice of a particular dialect, idiolect or register with which to render the speech of a character in the source text or the defendant in a courtroom is therefore potentially an ethical choice, one that has an impact on the way readers or hearers will perceive the character in question (and consequently the community they represent), the veracity of a defendant’s testimony, the reliability of a witness’s statement, or the credibility of an asylum seeker’s account of his or her persecution.

Another topic that might be considered of special ethical significance in translation and interpreting is volunteerism, including the growing tendency for non-profit and humanitarian organisations to solicit free translation and interpreting from students, who are often happy to undertake the work in order to gain experience and boost their CVs. Many professional translators and interpreters feel threatened by this practice and insist that it is irresponsible and unethical, with serious consequences for the profession. Aurora Humarán, one of the founding members of AIPTI (Asociación Internacional de Profesionales de la Traducción y la Interpretación/International Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters, based in Argentina),[18] outlines one rationale for this argument:

Does a dentistry student perform root canals? No. Does an architecture student build anything? Not a thing. Does a law school student defend anyone? No one.

Students from any of those career fields can, of course, perform some sort of work “within their areas” of study. A dentistry student can work as an assistant in a dental office. An architecture student can get a handle on his/her future profession by doing administrative work in an architect’s office. And anyone in the legal field is certainly aware of how many law students act as paralegals, traipsing from one court to another every morning.

In our profession, however, there is no place, really, in which translation students can learn to take their first steps. There is no such job as dictionary handler, word researcher, glossarist or anything of the kind for those who are trying their hand at these tasks for the first time. No such position exists. Well, let me correct myself: It didn’t exist. It didn’t, that is, until some slick operators threw together an agency – the way you might slap together a stand for a rummage sale – and (voila!) translation students suddenly had a place to work. So, let’s translate! But translate just like a professional translator? No way! This is cut-rate translation in which students do the work professionals usually do, but for ridiculous rates, turning themselves into veritable “beggar translators”.

She continues; “What we have here are cut-rate wholesalers who are exploiting the students, taking advantage of the students’ lack of experience and their willingness to start working, even when they are paid ridiculous rates that add up to next to nothing. This is utterly shameful and our greatest fear is for the students themselves”.[19]

By contrast, some argue that, managed judiciously and in the appropriate contexts, volunteerism in the case of translation and interpreting can be an ethical and socially responsible choice (Manuel Jerez et al. 2004):

In the association ECOS, Translators and Interpreters for Solidarity, we perform volunteer work of translation and interpreting for NGOs, social forums and other nonprofit organisations with affinities to the philosophy of our organisation. In no case would we wish to accept a continuous role in the performance of a service which ought to be supplied by professionals under contract.

In other words, we do not intend that the voluntary nature of work performed should serve as an excuse for the creation of what is beginning to be called a “third sector,” which would amount to the utilisation of volunteer work and non-profit organizations together with private initiative to organise, at low cost, services which in our opinion ought to be supplied by the public sector, the only one capable of the coverage necessary. … our work is like that of volunteers who supply medicines to third-world communities completely outside the trade network known as globalization.

… we consider it indispensable to broaden the concept of professional ethics in these times of neo-liberal globalization, which deepens the inequalities between peoples and within them. We can no longer limit our aims merely to defending decent working conditions and rejecting the intrusion of non-qualified persons into the profession. It would be hypocritical to bemoan the price per word paid by such-and-such a company, or the size of the interpreter’s booths in this or that convention centre, while feeling no scruples at working for those who organise exploitation, misery and war in this world.

Baker (2011:292-293) uses these two opposing statements as the basis of an exercise that can be undertaken in class to debate the issue from an ethical perspective.

A related topic which is beginning to attract much debate among professionals is crowdsourcing, or user-generated translation, as it is sometimes referred to (see section 1.4 above). This too might qualify as a core theme for a future translator and interpreter curriculum that is attentive to the issue of ethics, especially given its growing visibility and the controversies it has raised. As McDonough-Dolmaya reports (2012:168),

a recent report published by Common Sense Advisory … shows that one hundred organizations, including TED, Kiva, Twitter and Facebook, have resorted to crowdsourcing to meet their translation needs, confirming its impact on the way translations are performed and the extent to which non-professionals are becoming involved in translation.

An ethical engagement with this issue would explore both its potential negative impact on the profession, expressed in the petition by Translators for Ethical Business Practices mentioned earlier in this report (sectiion 1.4), and its potentially positive impact – in other words, the full spectrum of its ramifications for a wide range of constituencies. A recent report by the European Commission summarises the arguments for an against this practice. On the negative side (European Commission 2012: 38),

… serious concerns and fears are voiced both about the status and prospects of translators in the future, and about the quality of the work carried out by amateurs. The first concern is that translators will lose their source of income if translations are done for free by enthusiast amateurs. Secondly, many professionals blame crowdsourcing for being a weapon in the hands of companies to exploit and make profit from free labour. Finally, the issue of quality is regularly raised: how can we ensure high quality when the work is done by a crowd of non-professionals who most often than not lack specific qualification and expertise, are not clearly identified and, as a consequence, cannot be held responsible for what they publish on the net?

On the ethically positive side, the report has this to say (European Commission 2012: 36-37):

By promoting linguistic diversity on the Internet, notably giving access to information in languages usually disregarded for lack of economic impact, crowdsourcing favours inclusion and opens the Web to ethnic and social groups which would otherwise be excluded, thus fostering its democratic character.

Secondly, we can expect — and hope — that crowdsourcing, with communities gathering around a common interest or passion, will help dispel the common perception of translation as an invisible and rather dull activity we become aware of only where there is a problem, a chore carried out in dusty offices by isolated individuals always on the verge of losing contact with the world and their fellow individuals. The collaborative way of working highlights that, also in translation, constant sharing of ideas and experiences is essential to obtaining good results. Crowdsourcing can help raise awareness about the role of translation for the success of any initiative aimed at a large public. It can contribute to discard the perception that it is merely a sterile and repetitive task with no creativity involved, unclear purposes and doubtful usefulness, and show on the contrary that it is an essential tool to foster democracy and inclusion, offers great reward, helps break isolation and enables integration into a motivated and well-organised community, favouring contacts and exchanges with other people involved in the same activity and sharing the same interests and goals.

No doubt a number of other themes can be identified around which the introduction of ethics into the translation and interpreting curriculum can be developed.

3.3 Strategies

In addition to sensitising students to some of the main themes that raise ethical issues in their future profession, translator and interpreter training should also enable them to identify a range of potential strategies that may be deployed to deal with ethically difficult or compromising situations.

Some strategies that allow translators (rather than interpreters) to distance themselves from the content of what they are translating, where this content is morally reprehensible to them, are well known and readily available in certain genres and contexts, though not in others. They include the use of paratextual material such as prefaces, introductions and footnotes. For example, it is difficult to imagine a translator today rendering Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf into their target language without adding a preface or introduction that allows him or her to signal their ethical distance from Hitler’s claims and the values he promotes in this work. Hermans (2007: 54) offers an example of how an introduction to one translation of Mein Kamp, signed by the editorial team, effects ethical distance from its content:

The reader must bear in mind that Hitler is no artist in literary expression, but a rough-and-ready political pamphleteer often indifferent to grammar and syntax alike. […] Mein Kampf is a propagandistic essay by a violent partisan. As such it often warps historical truth and sometimes ignores it completely. We have, therefore, felt it our duty to accompany the text with factual information which constitutes an extensive critique of the original. […] The separation between text and commentary is clearly indicated, so that the reader will have no difficulty on that score. (Hitler 1939: viii-x)

As Hermans argues (1997: 54), “the way the translation is framed by editorial introductions and annotations highly critical of Mein Kampf emphasises the ideological divide separating translator and editors from Hitler”. Baker (2007/2010: 122-124) offers similar examples from Arabic translations of the late Samuel Huntington’s well known and highly controversial book The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, where the translators also frame the main text and signal their ethical distance from it through lengthy introductions as well as footnotes that comment on specific claims within the text.

Other strategies are available to interpreters specifically. They include the switch from first to third person pronoun in interpreting, as exemplified in Donovan[20] (2011: 119):

During a lunch discussion, a Brazilian participant began to justify the assassination of street children by paramilitaries. The interpreter, taken aback, introduced her rendition with “the speaker seems to be saying that….”, thus distancing herself doubly from the content. This is a clear and deliberate break with standard practice. Thus, by using the third person the interpreter indicates disapproval and in effect comments on the speaker’s remarks. … This would generally be perceived as an unethical rendition by the standards of professional practice. The distancing was possible because the interpreter felt her obligation of complete, impartial rendition was weakened by the non-representational (i.e. personal) nature of the statement and its occurrence outside the official proceedings.

Students can be alerted to these and other strategies and encouraged to debate the ethical implications of using them as opposed to merely following codes of practice that encourage them to refrain from intervening in the text they are translating or interpreting, whatever the context.

Other types of strategies that have received some attention in the literature, such as the use of cultural ‘equivalents’ to enhance the intelligibility or impact of a translation in the target context, can be revisited from an ethical rather than a purely linguistic or functional perspective to explore the potential, and pitfalls, they offer for resolving ethical dilemmas in specific contexts. Goodwin (2010) offers an extended and highly pertinent discussion of an authentic case in which a culturally opaque item in a documentary film is replaced in the subtitles by one that has resonance in the target context.

3.4 Pedagogical tools

In order to allow students to recognise and reflect on areas of ethical challenge in their future profession, and to rehearse potential strategies for addressing them before they have to encounter them in real life, educators need to develop a set of pedagogical tools that can be used to deliver appropriate training in this area. These tools must contribute to creating an environment in which students can make situated ethical decisions, rehearse the implications of such decisions, and learn from their mistakes. Activities within and outside the classroom can be designed to provide all three types of opportunity.

Classroom debate is one type of pedagogical tool that is particularly suited to the delivery of training in this area. It may be based on one of three types of material. The first is a hypothetical controversial issue, to be debated as a general ethical question; for example, the pros and cons of translating a particular type of text, or for a particular type of client. This type of activity offers many benefits: it exposes students to different values and ethical arguments that might diverge from their own; it encourages them to reflect on their own values and beliefs; and it helps them to develop general skills of debate, especially if the classroom activity involves them presenting and defending not only the position they themselves hold but also the counter position they oppose. The more controversial and sensitive the issue being debated the more useful the exercise. As Zembylas et al. argue (2010:563),

[i]nvestigations of the effects of teaching and learning about controversial issues show that if students have opportunities to discuss such issues in an open supportive classroom environment, they are more likely to develop positive civic and political attitudes, multiperspectivity, feelings of tolerance and empathy, and critical thinking skills.

Controversial issues might include themes such as whether or not translators and interpreters should agree to translate a text that promotes a practice or ideology they are deeply opposed to. What practice or ideology might be deemed ethically unacceptable will vary from student to student, but good examples might include widely debated and ethically challenging issues such as stem cell research (which offends those who believe in the sanctity of life in the womb), abortion, pornographic material, political speeches with racist undertones (such as those made in gatherings of the English Defence League in the UK), and same sex marriage.

In a recent issue of Multilingual which devotes much space to the question of ethics in the profession, Terena Bell, CEO of a Kentucky-based translation company, offers numerous such examples. She starts by posing the following question (Bell 2010:41):

If Blackwater[21] asked you to translate assembly instructions for an automatic rifle, would you do it? What if they told you the document’s target audience was teenagers in the Sudan? This is not a hypothetical, but a real dilemma my staff had to grapple with a few years ago.

She goes on to remind us that controversial issues are not restricted to questions of war and physical violence (Bell 2010: 41):

Military contracts and contractors aside, the language services profession is replete with controversial issues. If you’re pro-life, do you interpret for an abortion clinic? If you’re pro-choice, do you interpret for a crisis pregnancy center? And it doesn’t stop there. Legal interpreters who are against the death penalty may have to interpret judgments they don’t agree with, and feminist translators are asked to localize for adult entertainment.

Debating controversial issues should encourage students to consider the implications of either decision – to translate or interpret or refrain from translating or interpreting – within very specific contexts, since all ethical decisions must be situated. For instance, the decision as to whether it is ethically responsible to interpret for a far right speaker like Jean-Marie Le Pen of the French National Front Party, as Clare Donovan and her ESIT students concluded after much discussion, could depend on the venue of the speech.[22] Many students, and Clare Donovan herself, considered it unethical to interpret for Le Pen in a rally attended by his supporters, since this would help him promote his ideology in a context in which it would not be challenged. Interpreting a speech by Le Pen at the European Union, on the other hand, can be defended on ethical grounds since many delegates who can and arguably should challenge him in such a venue first need to understand what views he is advocating as accurately as possible.

Cohen (2010) discusses another controversial case in The New York Times which can be debated fruitfully in class and raises similar issues of situated decision making. He quotes a New York-based translator, Simon Fortin, describing an ethical dilemma he experienced:

I was hired to do the voice-over for a French version of the annual video report of a high-profile religious organization. The video opposes gay marriage, a view untenable to me. During the recording session, I noticed various language errors. Nobody there but I spoke French, and I considered letting these errors go: my guilt-free sabotage. Ultimately I made the corrections. As a married gay man, I felt ethically compromised even taking this job. Did I betray my tribe by correcting the copy?

Second, apart from controversial issues that have wide resonance in society, classroom debate can also focus on specific, preferably high profile authentic cases involving interpreters or translators departing from the codes of practice sanctioned by the profession and generally accepted as a given by society. Two examples can be cited here: Katharine Gun and Erik Camayd-Freixas.

Katharine Gun worked for the British intelligence agency GCHQ as a translator between English and Chinese until 2003, when she leaked secret documents to the Observer newspaper and was arrested for treason. The documents related to illegal activities by the United States and Britain in relation to the then impending invasion of Iraq. They exposed a highly secret memorandum by a top US official that outlined surveillance of a number of delegations with swing votes on the UN Security Council. The purpose of the surveillance was to gain information that can help the US to pressure members of the delegations in question to support a resolution in favour of the invasion of Iraq. In releasing these documents to the press, Gun violated one of the most fundamental principles enshrined in all professional codes of ethics, namely, confidentiality. She was later released following a major international campaign to support her, which involved high profile intellectuals and actors such as Sean Penn. Throughout her ordeal, Katharine Gun insisted that she did not regret her decision to divulge confidential information belonging to her employer, and that she had merely followed her conscience. Her action, she argued, was “necessary to prevent an illegal war in which thousands of Iraqi civilians and British soldiers would be killed or maimed” (quoted in Solomon 2003).

Erik Camayd-Freixas’s case is summarised in Baker (2011:285-286):

[He] was one of 26 interpreters called in to provide interpreting between US Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials and illegal immigrants arrested during a major raid on a slaughterhouse in Iowa in May 2008. In a long statement he published afterwards, he describes some of the harrowing scenes he witnessed when he and his fellow interpreters unexpectedly found themselves party to major abuses of the rights of these vulnerable immigrants.

Baker (2011: 286) goes to explain that Camayd-Freixas then found himself in an ethically challenging position:

He … had to weigh the ethical implications of ignoring injustice by simply walking away from it, as opposed to intervening to change the situation in the longer term. In an article about his experience that appeared in The New York Times (Preston 2008), he is reported to have ‘considered withdrawing from the assignment, but decided instead that he could play a valuable role by witnessing the proceedings and making them known’. He then took ‘the unusual step of breaking the code of confidentiality among legal interpreters about their work’ (ibid.) by publishing a 14-page essay describing what he witnessed and giving interviews about his experience. While maintaining his ‘impartiality’ during the assignment, to the best of his ability, he nevertheless arguably violated another professional and legal principle that could have had serious consequences for him personally, namely the principle of confidentiality.

This is a particularly interesting case study to debate in the classroom, because Camayd-Freixas has been very critical of the newspaper that broke his story and has insisted that he has not broken the code of confidentiality (Camayd-Freixas 2008):

The interpreter code of ethics, in particular the clause of confidentiality, has as its meaning and rationale that the interpreter must not influence the outcome of the case. The Postville case had been closed, and its 10-day deadline for appeal had expired before I even began the essay. I do not mention any names and aside from anecdotal information of a general nature, all the facts mentioned are either in the public record or freely available on the internet. So I was careful not to break the code of confidentiality.

Moreover, confidentiality is not absolute. There are other ethical requirements which override confidentiality. For example, a medical interpreter, in whom a patient confides that he has an epidemic disease, has the obligation to report it because it is in the public interest to do so. Similarly, in the Postville case, there were higher imperatives arising not only out of public interest but also out of the legal role of the court interpreter.

Debating authentic cases such as Gun’s and Camayd-Freixas’s allows students to rehearse the ethical arguments for and against specific behaviour that departs from established codes of practice within a clearly delineated context, and with considerable resources for rehearsing all sides of an argument. The literature on both these cases is extensive since they attracted significant interest from the media at the time. The grounds for debate can therefore be carefully prepared beforehand. A summary of the case can be circulated to students prior to the class session, together with a careful formulation of the question to be debated. Some links to sources of information may accompany the summary, but students should also be encouraged to conduct additional research to identify other sources. A post debate stage can further be built in, for example in the form of personal blog or diary reflections, or chatroom discussions on Blackboard.

Debating controversial issues and authentic cases that raise ethical challenges in the supportive environment of the classroom allows students to rehearse both sides of an argument freely, and to think through its ethical implications from different perspectives. Another way of achieving a similar but less interactive outcome might consist of writing a critical essay on a specific issue such as volunteer work or omission of material deemed offensive to the target culture. Alternatively, a critical essay might discuss one type of theorizing about ethics, such as Kantian ethics or Levinas’s notion of hospitality, and its implications for translation practice.

Yet another activity might take the form of role play as part of a simulated scenario in the classroom, a pedagogical tool particularly suited to interpreting practice and designed to prepare students for situations in which they have to make decisions very quickly, on the spot. Glielmi and Long (1999) provide a sample of such simulated scenarios, involving sign language interpreters working with rape victims. Simulated translation tasks, using authentic texts and briefs, similarly provide an opportunity for exploring the implications of a specific textual choice or series of choices; Floros (2011) discusses several such tasks.

Finally, student diaries or journals can also provide excellent opportunities for individual reflection on morally taxing situations, as discussed in Abdalla (2011).

4. Case Study: Introducing Ethics into the Curriculum at Leeds and University of East Anglia

Drugan and Megone (2011) offer one of the most detailed discussions of how ethics might be introduced in the translation and interpreting curriculum, with numerous examples of case studies and activities. Personal communication with the first author, Joanna Drugan (4 July 2013), confirms that at least some of the ideas outlined in this paper were put into practice at the University of Leeds, where both authors were based at the time – during the academic year 2010-2011 and, in a modified, less successful form in 2011-2012.[23] Since then, Drugan has moved to the University of East Anglia, where she intends to introduce ethics in the curriculum of the MA in Applied Translation Studies, specifically in a module entitled ‘Translation as a Profession’, during the academic year 2013-2014. This section reports on the most important features of these two experiments with embedding ethics into the curriculum.

First, in terms of the place and status of ethics training within the curriculum of the suite of MA programmes in translation and interpreting at the University of Leeds, Drugan reports the following:

It [the training in ethics] was first presented to them [the student cohort on all MA programmes in translation and interpreting) in a compulsory first-semester module, Methods and Approaches in Translation Studies. This module introduces all students to translation studies as a discipline, translation and interpreting theory, and research methods.

After the two-hour workshop[24] …, the students had a 6-week online course to work through at their own pace and time. They were split into seminar groups of 10-12 students, with a PhD student supporting each group via online discussion boards. Each group had a series of case studies, tailored to their programme of study. One or two cases were presented to them each week, sometimes in seminars and sometimes online.

In terms of how the students’ performance was assessed, a balance had to be found between ensuring that students took the task seriously and the need to start implementing the training plan as soon as possible, without having to wait for the outcome of lengthy processes of approval by the institution. This meant that the assignment could not be made compulsory. Drugan explains how the desired balance was achieved:

In order to be allowed to submit assessments for the module, they [the students] had to engage with the online groups and discussion, at least by reading and commenting once. Students who didn’t do this were contacted by the tutors. Although no mark was attached to the training, they could not proceed to completion of the module without this participation.

Chris [Megone] believes strongly, based on his wide experience of this sort of training, that there must be assessment/credit attached for students to take it seriously. Our plan was to test the approach and how well it fitted in terms of content, timing etc, then review this and apply for the right to make it credit-bearing. At Leeds, this was a lengthy process – it would have taken over a year. We were keen to get started so we decided just to go ahead then build up the training as we went.

It is worth noting here that sustained engagement with issues of ethics as a running feature of a programme requires collaboration across disciplines, as is evident in this case, with Chris Megone from Applied Ethics and Joanne Drugan from Translation Studies designing and overseeing the delivery of the relevant component of the syllabus. Megone and Drugan also had the benefit of assistance from PhD students at the Interdisciplinary Ethics Applied Centre in delivering the training to a large cohort of students,[25] as Drugan explains:

One PhD or post-doc student from the IDEA-CETL was assigned to each group (from memory, we had about 10 or 11 groups). The student ran the online training, first contacting everyone to prompt them to read and react to the first case study, then responding regularly to relate comments to the themes and issues raised by the discussion. Their aim was to place the students’ reactions in context, and offer suggestions for further reading or ways forward.

Drawing on her experience at the University of Leeds, Joanne Drugan plans to introduce similar training in the curriculum at the University of East Anglia in the academic year 2013-2014. She describes her plan as follows:

Next year, the ethics training here will sit in a Semester 2 module, Translation as a Profession. I’ll use a similar case study method, but this time only for translation students (about 20-30 per annum). The module is optional but is the basis for one of two ‘strands’ or pathways in the MA, running for the first time next year.

I hope to involve applied ethicists in some way – at the least, I will be inviting a specialist to do a workshop for the group, but I hope to track someone down locally who can get involved on an ongoing basis. It may be that this is a practising translator with an interest in ethical aspects of the role.

As is evident from Drugan’s experience, how and to what extent ethics can be introduced into the translation and interpreting curriculum is dependent on a number of different factors, not least the size of the cohort, the level of interdisciplinarity supported by the institution, the level of finance available for paying teaching assistants, organizing workshops and similar events, and – most importantly – the availability of a sufficient number of staff committed to this type of training to ensure that illness, study and maternity leave and similar factors do not disrupt the systematic and long term delivery of this vital component of the curriculum, as they did in Leeds.

5. Final Remarks and Recommendations

This report has offered a broad overview of the status quo and has made a number of detailed suggestions to support the introduction of ethics in the translation and interpreting curriculum. As evident from the discussion so far, the literature on ethics, like most of the literature on translation and interpreting, has traditionally assumed that translators and interpreters are primarily responsible to their clients, or the author of the source text in the case of literary translation in particular. This report argues that translators and interpreters have an ethical responsibility to other participants and to the wider community, over and above their responsibility to clients and authors. To what extent training should prepare students to act responsibly as citizens, rather than merely as professionals, is an issue that has rarely been broached by educators.

Introducing ethics into the curriculum raises a range of challenges for educators. Effective training in ethics must involve reconfiguring the classroom as an open, supportive space for reflection on potentially controversial and divisive issues, with educators refraining from prescribing or even recommending particular ethical paths. This clearly makes the issue of assessment problematic. On what basis, and according to what criteria, can educators assess the performance of students in terms of ethical decision making? One answer might be that educators should develop assessment criteria that focus on the quality of reasoning and reflection, and the extent to which the student engages with an ethical issue from different perspectives, rather than the final decision reached. This issue however merits further exploration.

Another issue to be addressed in the course of introducing ethics in the curriculum relates to the scope of the discipline and what we acknowledge as ‘the profession’. The question here is whether training should focus only on the prototypical, trained professional who chooses translation and/or interpreting as a career, or address the wider context and include volunteer translation and interpreting, as well as paid translation and interpreting undertaken by untrained people in war zones, for example. In situations of violent conflict, translation and interpreting are undertaken by a wide range of professionals, from doctors and engineers to taxi drivers and civil servants, as one of the few means of earning a living. InZone, the University of Geneva project discussed in section 1.3 above, has taken the position that untrained interpreters in crisis zones are part of the translation and interpreting community and entitled to training, including training in ethics. This is a position that the current report supports.

Yet another challenge that educators will face in the context of incorporating ethics into the curriculum concerns the persistent gap between theory and practice in the discipline. Translation and interpreting students are often resistant to theory, especially at the beginning of their degree programme, and may fail to see the connection between abstract theoretical concepts and everyday professional reality, as they envision it at that point of their career. This resistance may extend to reflection on the ethical implications of their translational choices. However, using authentic, real life case studies and introducing interactive tasks in the classroom should demonstrate to students the relevance of ethics and the liberating effect of being able to reflect on the impact of their behaviour on others. Boéri and de Manuel Jerez (2011) report that interpreting students’ evaluation of speeches by representatives of social movements and those on topics such as the relationship between poverty and war is particularly positive. This suggests that engagement with issues that raise difficult ethical questions can motivate students and demonstrate the importance of theory and reflective, critical reasoning.

Addressing these challenges and delivering effective training in ethics will require interdisciplinary collaboration and institutional support. It would benefit considerably from an institution such as the Higher Education Academy taking the initiative in establishing networks and providing relevant resources to allow the discipline to move forward on this front.

6. Recommended Reading

Baker, Mona (2008) ‘Ethics of Renarration: Mona Baker is Interviewed by Andrew Chesterman’, Cultus 1(1): 10-33.

Baker, Mona (2011) In Other Words: A Coursebook on Translation, second edition, London & New York: Routledge (Chapter 8: Ethics and Morality).